Yesterday, we learned how a guy named M. King Hubbert introduced the concept of peak oil in 1956, a concept that peaked in the public psyche somewhere around August 2005.

Today, we’re returning to the question, “Whatever happened to peak oil?” – which is the moment oil production reaches a global maximum.

Did peak oil already happen?

Maybe. Here’s what global oil production looks like over the past twenty years:

Peak oil could have happened yesterday, or last month. It might happen tomorrow, or next year, or in five years, or twenty. We won’t know when it happens; we’ll only know in retrospect.

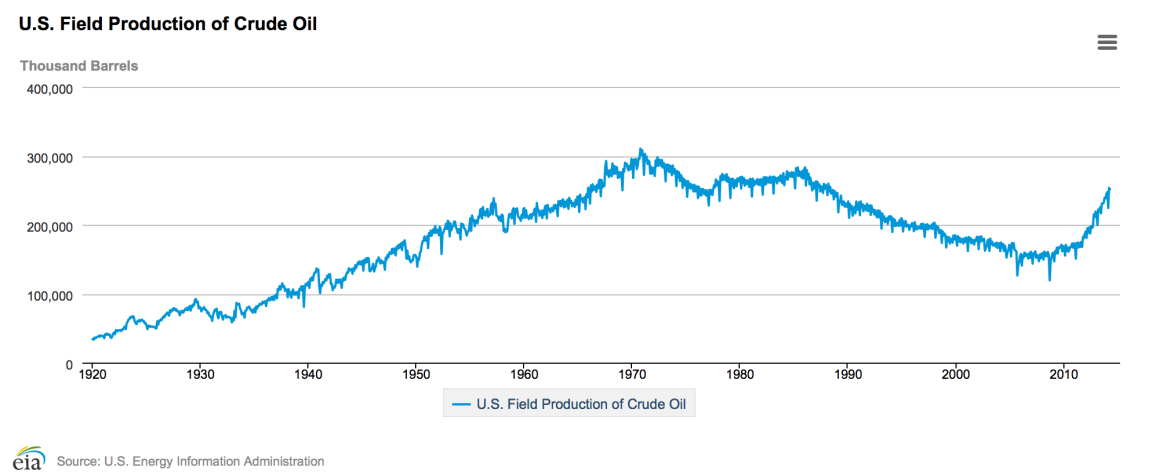

Even then, we may think we’ve peaked and then realize we haven’t. That’s exactly what happened in the U.S., which peaked in the 1970s – until we starting mining oil from shale. Now, U.S. production is up and refineries are running at record levels.

Energy Information Administration

U.S. oil production looked like it peaked in the 1970s, but is seeing an upsurge due to recent oil shale extraction.

Is peak oil “real” and is it something we should be worried about?

As the U.S. Department of Energy said in a 2005 report, “Oil is the lifeblood of modern civilization.” Experts have described all kinds of cascading end-of-days scenarios for when that blood runs dry: higher oil prices leading to a major recession, a drop in agricultural production leading to global famine, a complete disruption of life as we know it.

Obviously that hasn’t happened yet, and peak oil prepping has gone out of style (although you can still pick up guidebooks on getting ready for the impending disaster).

The peak oil debate has produced optimists and pessimists. There are peak-oil-deniers (lots of them) and peak-oil-denier-deniers. Some argue that even though oil discovery peaked fifty years ago, we’ll keep developing technologies that will allow us to get harder to reach reserves and so oil production won’t peak, or alternative energy sources will preempt it. Others claim that the market – supply and demand – will take care of peak oil for us, and before we run out of oil to extract, it will become too expensive and won’t be worth it to mine anymore. Or, some say, the problem isn’t peak oil, the problem is us. George Monbiot wrote, in 2012, “There is enough oil in the ground to deep-fry the lot of us, and no obvious means to prevail upon governments and industry to leave it in the ground.”

Perhaps peak oil is a red herring. Instead of debating if or when it will happen, or if it already happened, or why it will never happen, we should be asking:

How will we meet our energy needs in the future, and can we do so in a way that doesn’t cause harm?

Peak Vernacular

Whether or not we’ve reached peak oil, and whether or not peak oil is a huge apocalyptic deal, the concept of peak something is embedded in our cultural vernacular. Andy Revkin of the New York Times has long discussed the concept of “peak us” (human population) versus “peak everything” (resources) – peak water, and peak food, and peak lithium.

But the concept of peak has gone beyond resource use and attained meme status: There’s peak Internet, and peak Catfish, and peak bacon, and peak traffic signs, and peak hipster.

Google search is pretty sure I’m more interested in peak beard than peak oil.

Peak oil has left us a lasting legacy: the real sense that stuff isn’t infinite. Things – from oil production to our cultural obsession with Fifty Shades of Grey – don’t just grow forever. They peak and they decline. This seems like a basic concept, but it’s surprisingly revolutionary when you consider how many measures our economic and societal well-being are based on growth. So thank you, M. King Hubbert, not just for peak oil, but for peaks everywhere.