Get the data: CSV | XLS | Google Sheets | Source and notes: Github

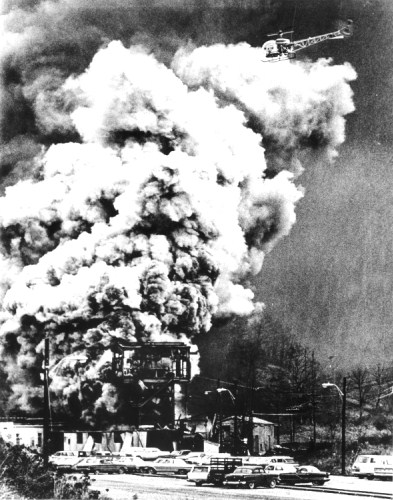

Wikimedia Commons

Fire and smoke pouring from the Consol No. 9 mine in Farmington, West Virginia following an explosion on November 20, 1968.

It’s no secret that the oil and gas industry is dangerous. As the industry has grown to employ over half a million oil and gas workers nationwide, the number of fatalities has grown as well. Last year, 112 oil and gas workers died on the job; the year before, 142. Nationwide, oil and gas workers are still six times more likely to be killed on the job than the average American.

In 2011 and 2012, Texas had the most fatalities overall–106–but, according to new analysis by Inside Energy, North Dakota had the highest fatal injury rate in the country–75 deaths per 100,000 workers. That’s three times higher than the national rate for oil and gas fatalities.

We wanted to know: how many is too many? Or, put another way, how bad does it have to get before regulators and elected officials step in and do something?

That’s exactly what happened in 1968 after the Farmington No.9 coal mine in West Virginia blew up. Smoke billowed from the mine’s entrance for 10 days as emergency responders tried to reach 78 trapped miners. Then, with people all over the country watching on the nightly news, they gave up and decided to seal the mine–with the miners inside.

Afterwards, a group of miners’ widows went to Washington D.C and testified before Congress. They asked them to do something to make mining safer.

“They were lamenting the safety issues that their husbands had told them about over and over again,” said Bonnie Stewart, a journalism professor at California State University Fullerton and the author of a book about the mine disaster.

“Several of them had told their families, ‘this mine is going to blow.'”

A month later, the Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, referenced Farmington No.9 as he threw down the gauntlet in a speech on mine safety.

“Let me assure you,” he said, “the people of this country no longer will accept the disgraceful health and safety record that has characterized this major industry.”

After the disaster, Congress passed the 1969 Coal Mine Health and Safety Act, which required more mine inspections and upped the consequences for violations. Eight years and multiple mine disasters later, Congress went even further, creating the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

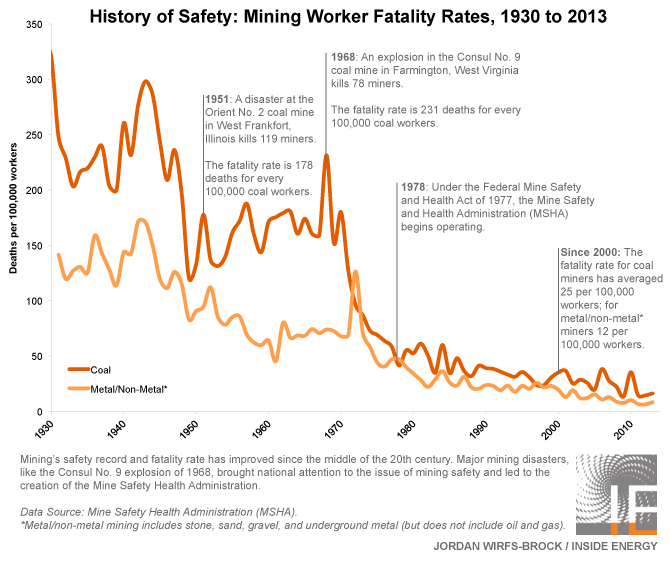

Coal mining has gotten a lot safer since then (check out our database). In the 1960s, the fatal injury rate was 174 per 100,000. In the 2000s, that dropped to 27 per 100,000–a decrease of 84 percent.

Today, it’s more dangerous to be an oil and gas worker than a coal miner. But these deaths rarely get more than a one-paragraph write up in local papers like the Casper Star-Tribune or the Dickinson Press.

Peg Seminario, director of safety and health for the AFL-CIO, said the deaths are easy to overlook because they happen one by one. “They don’t get the same kind of attention as a disaster in a coal mine, where you have multiple miners that may be killed. Nonetheless, the worker who’s working in oil and gas is more likely to be killed on the job than a coal miner. That’s a fact.”

This is not a new problem. In 1983, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration acknowledged the dangers of working in oil and gas and even admitted it wasn’t doing a good job regulating the industry. On December 28 of that year, the agency printed a lengthy notice in the federal register announcing it was planning to create separate regulations for the oil and gas industry.

“OSHA believes that the current general industry standards inadequately address the unique hazards encountered during drilling, servicing and the performance of special services operations on oil and gas wells. OSHA believes this lack of adequate regulatory protection has contributed to the high number of deaths and injuries in this industry.”

Eric Brooks, area director of OSHA in the Dakotas, keeps a faded copy of that federal register on his desk.

“It reminds me that even 30 years ago we had recognized a need for specific regulations,” he said. “When we look back at what drove this particular need, I have to believe the same conditions still exist in some areas.”

But, OSHA never did create separate regulations for oil and gas. In fact, oil and gas companies enjoy many exemptions to federal safety standards, including exemptions for noise and benzene pollution. Brooks believes the lack of action is due to a regulatory process that simply takes forever. Others say the oil industry has a lot of clout.

But Ellen Smith, editor of Mine Safety and Health News, has another theory. Back in the 1970s when Congress decided to make mining safer, she said, people had a lot more faith in government regulations. Now, legislative action is more likely to happen at the state level than the federal.

In fact, a few states have tried to make dangerous industries safer. Alaska did it with commercial fishing and aviation in the 1990s. Wyoming has started to address its oil and gas problem. But other oil producing states, like North Dakota, haven’t really tried.

So, what’s the tipping point when an industry becomes so unsafe, something has to change? That’s what we’ll be looking at in stories to come in this series.