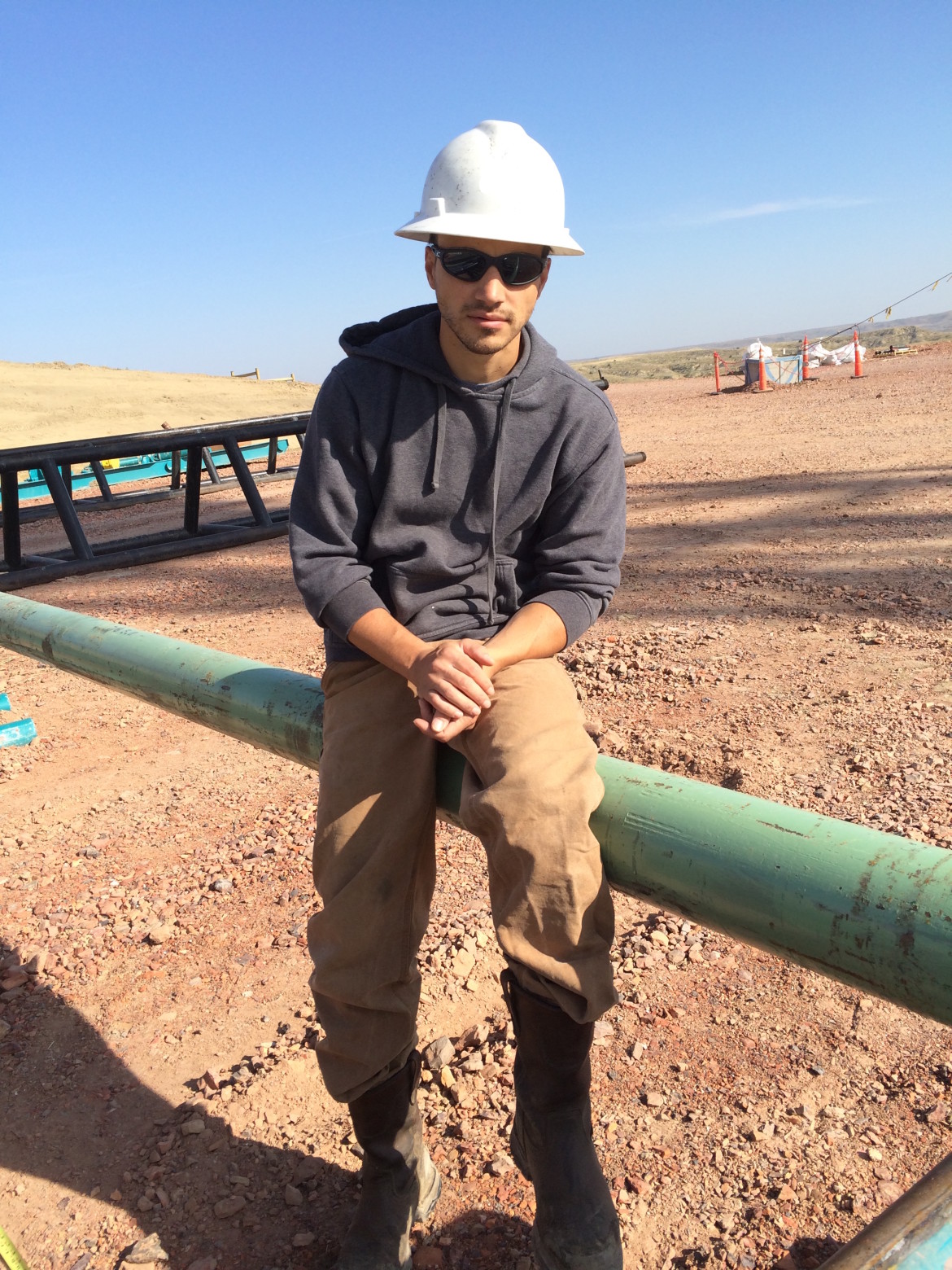

Neil LaRubbio

Neil LaRubbio on the job site.

PRODUCER’S NOTE: When oil prices fall, like they’ve done over the last six months, one of the first things oil companies do is cut back on workers and on the number of drilling rigs. That’s happening around the country: There are about half as many rigs in March as there were last September. Fewer rigs means more competition for jobs on drill sites. We asked Neil LaRubbio to tell us what it’s like to be one of those oil workers fighting to keep his place in the industry. His account is below.

I’ve spent two years living on an oil well pad in a single-wide trailer as cramped like an airplane fuselage. A constant drone of diesel engines seems to cordon us off from the outside world.

I survey oil wells, which means I operate a kind of compass that directs the drill bit and maps the rock strata. After setting that compass in the hole, I stare at a computer for hours, as the drill digs its way down. Workers on the well pad call people in my position: “The Movie Watching Dude.”

I share the trailer with another surveyor and two drillers. We can be on the same well pad in the same “fuselage” for months on end. We peck at each other out of insecurity. Or out of boredom. Or just for sport to pass the time.

The oilfield was a reasonably comfortable place to work — the guys on my team are all earning somewhere between $400 to $800 a day — until the end of last year, when oil prices started to tumble. Now, they’re below $50 a barrel.

We constantly wondered if we were all out of jobs for the rest of the year. My co-worker, Dale Thompson, thought: If it gets up into the $60s, work will pick back up.

I’m not so sure. Our service company has been trying to hold on to as much work as possible. We heard rumors that the oil company that hired our services wanted to replace us with a cheaper company. And one day recently, while drilling a well just outside of Denver, it happened. A company from Louisiana outbid us. Dale was not happy. He hoped, as we all did, that the Louisiana company would fail, and our jobs on the well pad would be restored.

“A buncha **** asses are coming out here to do our jobs,” he said the day we found out. “They can’t do it, well, because we’re better. We’re from Texas.”

He was probably right. We cut nine days off last year’s drill time. We just drilled a five-day well. But that didn’t seem to matter to the company that hired us.

“It’s going to be about money,” Dale said. “How much money can you put in my pocket?”

None of us know when we’re going to get work next. And when we do, it probably won’t be anywhere near here. While we did end-of-job chores, we stewed on what was happening.

My co-worker Andrew said this might be goodbye to the oilfield. “I was never cut out for this anyways,” he said.

I joked about sinking into a depression hole, knowing that wouldn’t change a thing.

We started packing up. Bedding, clothes, protein powders, dumbbells, and whatever else we had accumulated. None of us are good at goodbyes, so when we were done we just drove off.

Leaving the well pad, I feel like a red-eyed gambler walking away from the casino. I’m exhausted from 35 straight days of work; from sleeping during the day, rather than night; from adrenaline spikes when the pressure is high. And now, there is no work in sight. The money illusions have dissipated. I’m trying to ignore that lost feeling. It’s time to re-acclimate to society and home life again.

When I get home, I find my son, Nico, nursing a cold in bed. He asks me if I’m going to work today.

No, I tell him. I’m going to stay home for a long time.

This radio diary was produced by Inside Energy reporter Emily Guerin.