Flickr user Geof Wilson

Pumpjacks outside Tioga, North Dakota.

The oil and gas industry pays a ton of money in severance taxes to energy producing states like Colorado, Wyoming and especially North Dakota. When oil prices were high, North Dakota took in about $10.5 million a day. But as prices have fallen, so has revenue. In the midst of this, North Dakota lawmakers have passed a bill to stabilize and lower the state’s oil and gas tax rate.

Very few people in the state capitol of Bismarck support the state’s current tax system. Representative Al Carlson, the House Majority Leader, put it this way:

“It was once explained to me that our tax policy is kinda like being on the wheel of fortune,” he said. “Because sometimes you can hit the big trip to Hawaii and the next spot can be bankruptcy.”

In North Dakota the oil and gas tax rate is pegged to the price of oil. When prices are high, companies pay about 11.5 percent on the value of oil produced. When prices are low for an extended period of time, they pay 5 percent. So in April, Carlson introduced House Bill 1476, which was designed to get rid of that volatility.

“We thought it would be beneficial to have a stable tax system both for the state of North Dakota and for the industry,” he explained.

Here’s how it will work: The enormous tax cut that lowers the rate to 5 percent disappears forever towards the end of this year. On January 1, 2016, the overall rate drops from 11.5 to 10 percent. And there’s a new trigger, one that raises the rate back up to 11 percent if the price of oil stays above $90 for three months in a row.

Severance taxes vary wildly from state to state. There are places like Alaska, where oil companies can pay over 20 percent of what they produce to the state. Then there are states like Oklahoma where companies pay about three percent. There are also a million different exemptions and tax holidays that mean companies can pay different tax rates on new wells, old wells, wells that don’t produce much or wells outside a developed oilfield. All that makes it very hard to get an apples-to-apples comparison of severance taxes.

Still, there are some conclusions we can make. Barry Rabe, professor of public and environmental policy at University of Michigan, studies oil and gas taxes. He has found that states that were earlier players in oil and gas tend to have the highest rates.

Take Wyoming, where oil was discovered in the 19th century. Companies there pay one of the highest tax rates in the lower 48 — just under 12 percent. That means if oil sells for $100 a barrel, Wyoming collects about $12 per barrel. Compare that to newer energy states like Ohio, which collects only 20 cents per barrel of oil they extract, no matter the price.

Ironically, states we tend to think of as most hostile toward taxation tend to set the highest rates, Rabe says.

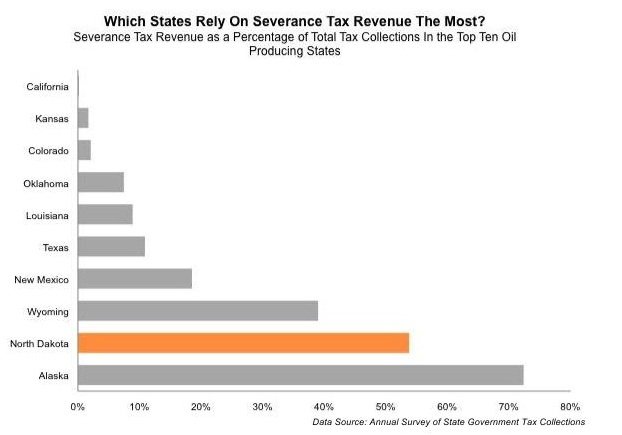

Mark Haggerty, a researcher with Headwaters Economics, a nonpartisan research group in Montana, says there is a reason for this. He says Wyoming has made a conscious decision to use its natural resources to fund state government and lower the tax burden on its citizens. As such, it needs to tax the industry heavily. Severance taxes make up 40 percent of total tax collections in Wyoming compared to only two percent in Colorado, a state with a much more diverse economy that is much less dependent on natural resources.

States like Wyoming and North Dakota are, “very dependent on the industry, they need the industry, but they’re also willing to be more aggressive in taxing the industry than their neighbors,” according to Haggerty.

Get the data: CSV | XLS | Google Sheets | Source and notes: Github

But the shale boom is starting to change that. Now that fracking and horizontal drilling are unlocking reserves in unexpected places like Ohio and Michigan, there’s more pressure to try to compete with other states for oil companies’ business. North Dakota Senator Rich Wardner, R-Dickinson, made that argument before the House Finance and Taxation Committee while testifying in favor of lowering and stabilizing the tax rate. When the price of oil drops, he said a lower rate will cause companies to “stick around longer and there will be more activity out there.”

But many researchers disagree with Wardner’s argument.

“There’s not a lot of evidence, empirically, to suggest that drilling investment follows tax rates, especially when we’re talking about a few percentage points,” Rabe says. “And yet that still comes up in the minds of a lot of legislators who are thinking about how to best cultivate a resource.”

Whether there’s evidence for that or not, legislators are grasping for ways to stimulate an industry that’s facing a very different future than it was just a few months ago.

What’s Next:

- Wanna know how much tax revenue an oil well in the Bakken generates compared to the Eagle Ford, Niobrara or other oil-producing regions? Headwaters Economics has you covered.

- Read this study comparing how much tax revenue oil-producing states return to local communities.