Jack Amick via Flickr

The traditional Thanksgiving Day meal might be a belt-buster, but it won\’t bust your carbon footprint score.

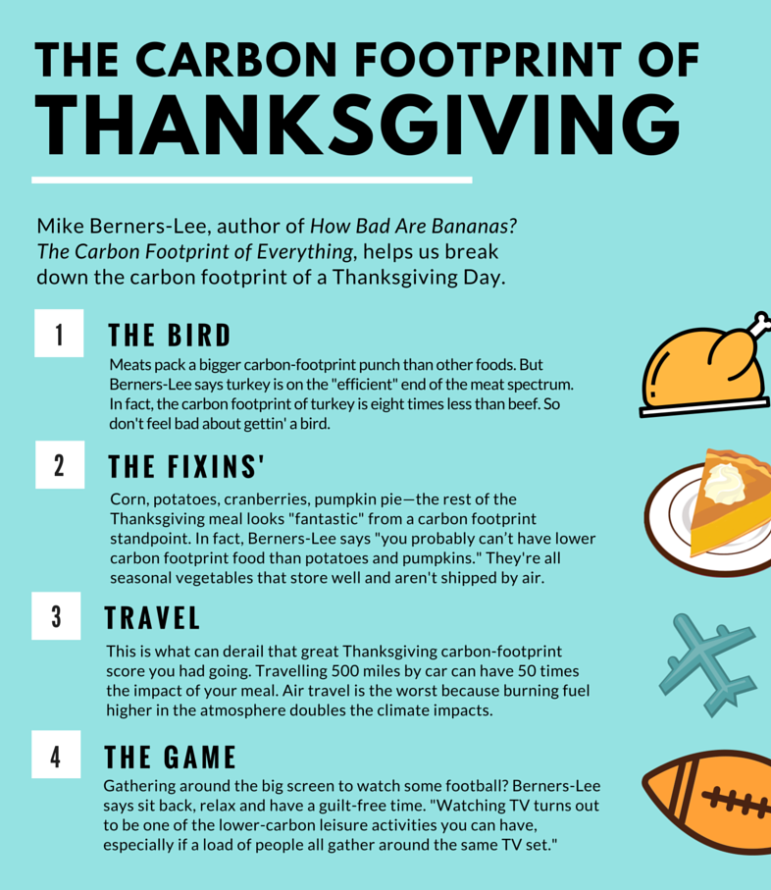

Mike Berners-Lee may not be an expert on the American Thanksgiving. A native of the UK, he’s never actually had the pleasure of experiencing one. But as one of the world’s leading researchers on the carbon footprint of—well—everything (he even wrote a book subtitled “The Carbon Footprint of Everything”), he’s plenty familiar with the impacts of the foods that star in the traditional Thanksgiving Day spread.

“Well, turkey is a meat. And most of the time, the thing to say about meats is that they’re quite an inefficient way of having nutrition,” says Berners-Lee. “But having said that, chickens and turkeys are very much at the efficient end of the meat spectrum.”

That’s because a Thanksgiving turkey can go from egg to a bird that’s 20 pounds or more in just 14 weeks. So they’re not really on the planet long enough to make that big an impact. And it turns out it doesn’t even matter all that much if you go with a local bird that only has to ship from the farmer down the road.

“Well, it matters a bit. But it would still be fairly small compared to the actual footprint of growing the animal in the first place.”

In fact, Berners-Lee says transportation might only account for 25 percent of your turkey’s total carbon footprint—assuming it’s not shipping by air. But bottom line, having a turkey on your Thanksgiving table is not all that bad. And the same goes for corn, potatoes, cranberries, pumpkins and a lot of the other foods that end up on your plate.

“They’re seasonal vegetables. And they keep well,” says Berners-Lee. “And you don’t have to do anything crazy like put them on an airplane. So they’re fantastic. In fact, you probably can’t have lower carbon footprint food than potatoes and pumpkins.”

So all in all, the Thanksgiving dinner looks pretty good from a carbon footprint standpoint. That is, if you go traditional.

“This year is a little bit of a curveball,” says WESA reporter Margaret Krauss, who agreed to let us dissect the carbon footprint of her Thanksgiving plans. “But there is no turkey. There is a meat that will be grilled outside. Maybe we’re doing bratwurst, maybe we’re doing chicken, maybe we’re doing steak.”

And the alternative menu could get Margaret into some carbon-footprint trouble according to Berners-Lee.

“Yeah—red meats are quite a lot less efficient. The carbon footprint of beef would be about 24 kilos of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilo of beef. Whereas for turkey, it’d be nearer three.”

And the air travel involved in Margaret’s Thanksgiving celebration—a flight from Pittsburgh to Salt Lake City—is a real killer.

“So a Boeing 747 will get through a hundred and something tons of fuel per trip,” says Berners-Lee. “So you end up with an enormous carbon footprint shared out between the passengers. And your friend has to take a few tons of it on the chin.”

Even worse, Berners-Lee says the fact that the fuel is burning higher up in the atmosphere doubles the climate impacts. So drive if you can. Better yet, take a train. But how does the carbon footprint of Thanksgiving travel stack up against the Thanksgiving meal? It’s not even really much of a comparison. Berners-Lee says for a 500-mile trip, you’d have to eat more than 100 pounds of turkey to match the impact of your travel.

“That would be quite an achievement,” Berners-Lee says.

As for the other major item on the Thanksgiving Day schedule—watching football—Berners-Lee says that’s a pretty guilt-free activity.

“Everyone assumes the impact is going to be really high,” he says. “But watching TV turns out to be one of the lower-carbon leisure activities you can have—especially if a load of people all gather around the same TV set.”

This story comes to us courtesy of Allegheny Front, a news magazine on the environment in Pennsylvania.

What’s Next:

Check out Mike Berners-Lee’s book How Bad Are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything.