Ingrid Lobet / inewsource

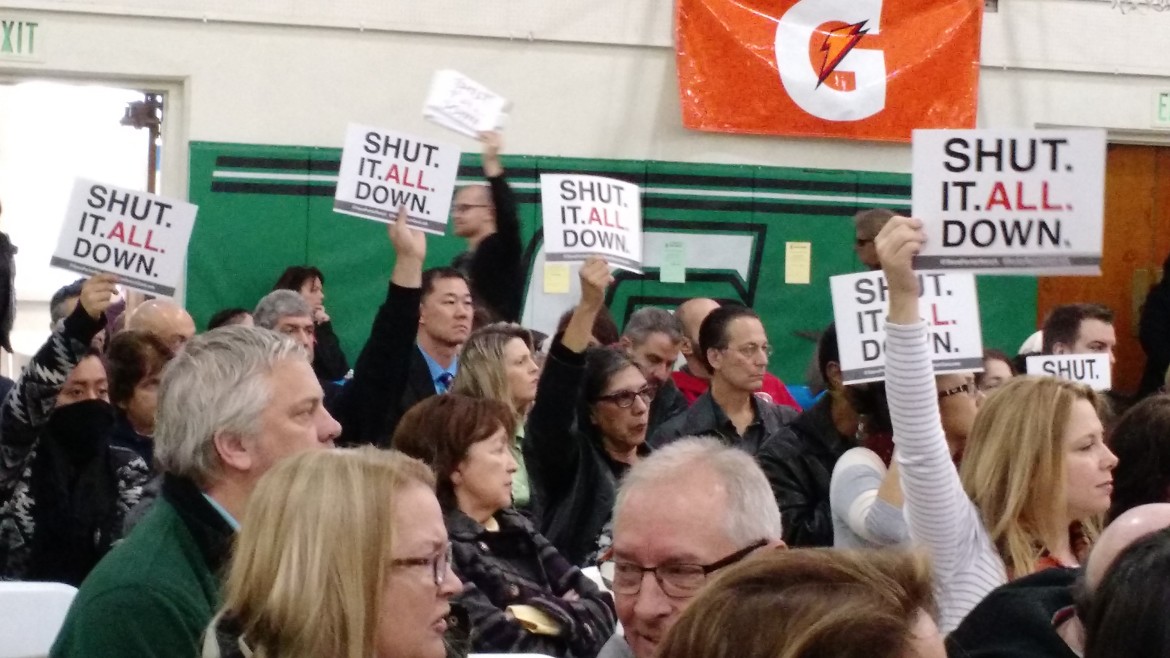

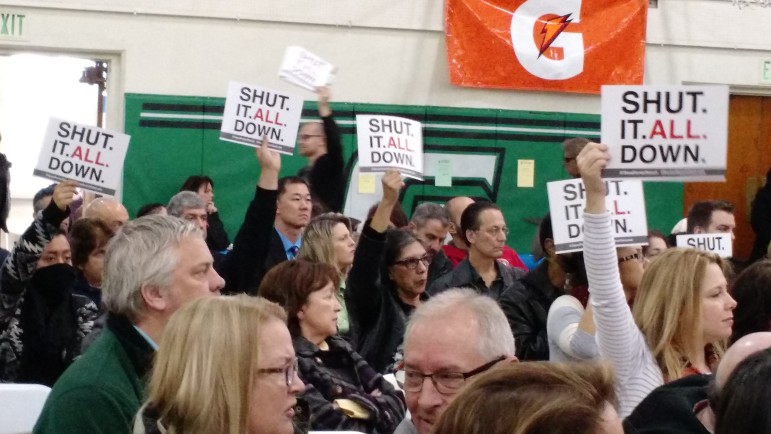

Signs like these asking for the complete closure of the Aliso Canyon Gas Storage facility, which Southern California Gas considers an essential asset, are beginning to appear at rallies held by residents of Porter Ranch.

A blown out natural gas well in Los Angeles has been pouring methane into the air for over two months now. It’s estimated that each day the Aliso Canyon leak is adding about as much greenhouse gas to the atmosphere as four and a half million cars on the road. The spewing gas is sparking calls for a new watchdog system for methane.

The out-of-control well has prompted more than 2,800 families to evacuate their homes. Two elementary schools have temporarily shut down. Some residents are calling for Southern California Gas to close down its biggest gas storage field.

Ingrid Lobet / inewsource

Marine veteran Brian Seligman said the smell of gas in Porter Ranch bothers him even when he takes his children to Hebrew school there. He lives in Simi Valley, and attended a recent hearing on the gas leak.

The gas escape is causing policy changes. Last week the governor of California told his oil and gas chiefs to come up with emergency controls for gas storage fields, like daily inspections with infrared cameras that can see the invisible gas, and inspections of safety shut-off valves. The problem is, safety shut-offs are often not required on these kinds of wells, according to Anneliese Anderle, who worked in oil and gas for 40 years.

“The only ones that are required on land are critical wells that are close to airports, residential areas or streams,” said Anderle.

But that, she predicts, is going to change. Many more wells will now have to have safety shutoffs, just like your gas line. She also believes new laws are coming, at least in California, that will require testing the actual condition of old steel well pipe, or casing.

“The tests that are being done now are very superficial,” she explained.

Some experts believe the changes need to go well beyond California. Mark Brownstein is with the Environmental Defense Fund. He said every state oil and gas regulator should be looking at their storage facility programs. The EDF has sponsored numerous investigations of methane leaks in the country’s oil and gas industry. The gas hissing out of wells, pipelines, compressors – everything from the well to your local pipe. What they’ve found is not reassuring.

Natural gas production and demand don’t necessarily move together, so millions of cubic of feet of natural gas are stored underground for future use. The Aliso Canyon facility in Southern California, currently leaking massive amounts of methane, is one of the largest facilities, but it’s not unique. This map shows the more than 400 underground storage facilities nationwide (blue and green circles), as well as major interstate natural gas pipelines (grey lines). Larger circles indicate larger facilities. Click on a storage facility to find out information like the type and capacity. Only a small fraction of facilities, indicated in green, are required to report their measured methane emissions to the U.S. EPA. Data source: EIA, EPA.

In one study Professor Anthony Marchese of Colorado State University looked at 130 facilities where natural gas is gathered and processed. About one out of five was leaking…a lot.

“That’s what we call ‘super-emitting facilities. The highest emitting facility was about 1,000 kg/hour. This one, Aliso Canyon is 50 times larger than the largest leak we saw,” said Marchese.

The federal government could broaden a Colorado law that requires more testing and more leak-fixing of natural gas facilities. Brownstein of the EDF said they believe that should happen.

Trade groups representing the gas industry declined to make someone available to comment on this story. But just last fall the American Petroleum Institute issued a 50-page set of best practices for gas storage fields. Javier Mendoza, a spokesman for Southern California gas, said their maintenance system is already strong:

“You know we already have a monitoring and maintenance system that is robust and methodical. And one of the things that we regularly do is look at new technology,” he said. His best current estimate for when this well will cease its methane flow – late February.

This story comes to us from inewsource, an independent investigative news organization.

What’s Next:

- The EDF just released a report Rising Risk: Improving Methane Disclosure in the Oil and Gas Industry

- See our previous coverage of this story here, and a post showing the massive size of our natural gas infrastructure.