It came as news to Jeff Parsek that state records show there is an abandoned oil and gas well in his driveway. Parsek lives in a large, brown ranch house, right across the street from an elementary school, in a subdivision on the south side of Fort Collins, Colorado. It’s a nice neighborhood, with the new feeling of many Colorado suburbs.

When Parsek bought the house in 2004, he didn’t ask about oil and gas wells on the property.

“I wouldn’t have even thought to research that,” he said. Other homeowners I met in my search for abandoned wells responded with curses and slammed doors—one yelled, “thanks for ruining my afternoon!” When I told Parsek about the well, he just shrugged.

“If it started to emit something, then I might [be worried],” he said. “But to this point I’m not concerned.”

The trouble is, it might be hard to know if the well were emitting something. When a well stops producing commercial quantities of oil and gas, companies ‘abandon’ it, usually by placing cement plugs inside the wellbore, to stop the flow of gas and fluids. The industry considers that the end of the life of a well.

“It’s not rocket science to plug these wells,” said Wyoming Oil and Gas Supervisor Mark Watson. “It’s a hole in the ground that’s pretty deep. You set cement, and cement lasts a long time.”

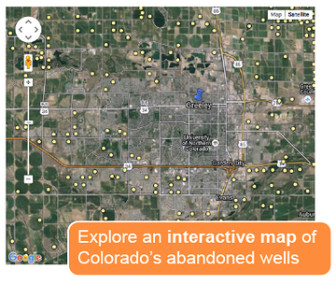

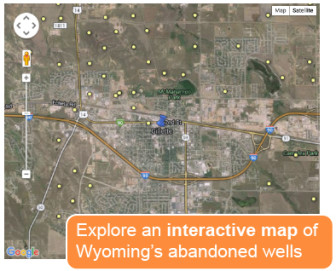

That conventional wisdom—that a well is dead once it is plugged with cement—means there’s no systematic monitoring for leaks of any of the millions of abandoned wells in the U.S. Colorado alone has more than 35,000 abandoned wells; Wyoming, more than 50,000.

“When a state sees a well is plugged, they typically put a checkmark by that well in a database, or in a file somewhere, and they don’t do anything [else],” said Rob Jackson, a scientist at Stanford University.

Unless a well starts leaking fluids or a house blows up, the assumption is that everything is fine. But recent work by Jackson’s research group challenges that idea.

Methane is the main component of natural gas, and it is present in every oil and gas well. It’s also a potent greenhouse gas that’s potentially explosive when it accumulates in confined spaces. In Pennsylvania and California, Jackson and his colleagues have tested abandoned wells, both plugged and unplugged, for methane leaks. The results are surprising; in most cases, the wells were leaking extremely small quantities of methane, but a few wells were leaking several orders of magnitude more. It wasn’t just the unplugged wells. Some of those ‘super emitters’ had been plugged.

Methane is the main component of natural gas, and it is present in every oil and gas well. It’s also a potent greenhouse gas that’s potentially explosive when it accumulates in confined spaces. In Pennsylvania and California, Jackson and his colleagues have tested abandoned wells, both plugged and unplugged, for methane leaks. The results are surprising; in most cases, the wells were leaking extremely small quantities of methane, but a few wells were leaking several orders of magnitude more. It wasn’t just the unplugged wells. Some of those ‘super emitters’ had been plugged.

Even those super leaky wells, from what we know, are emitting is far less than, for example, the massive leak in southern California, but they do add up. In Pennsylvania, one of Jackson’s colleagues, engineer Mary Kang, estimated that abandoned wells account for 4 to 7 percent of the state’s total man-made methane emissions.

The Canadian province of Alberta, the energy center of that country, requires companies to monitor some abandoned wells. They’ve found that on average, 7.7 percent of wells end up leaking.

But whether those results translate to Wyoming and Colorado is hard to say, since no one is looking for leaks. Stanford’s Rob Jackson thinks it’s partly an issue of states not having the resources to monitor.

But whether those results translate to Wyoming and Colorado is hard to say, since no one is looking for leaks. Stanford’s Rob Jackson thinks it’s partly an issue of states not having the resources to monitor.

“But I also think the states aren’t that interested in some cases, in many cases, in the data. I’m not sure they really want to know,” he said.

Then again, even if authorities were interested, they’d probably have a hard time tracking down old wells. Once a well is plugged with cement, it is cut off below-ground, covered up with dirt and then, more often than not, never thought of again. Sometimes, a dead well is marked with a tombstone of sorts, a marker listing its unique identifying number, but often there’s no indication whatsoever on the surface.

Stephanie Joyce / Wyoming Public Media

Liquid cement pours out of the top of a well that is being plugged and abandoned.

That’s what Inside Energy data journalist Jordan Wirfs-Brock and I discovered on a recent afternoon when we went searching for abandoned oil and gas wells around Fort Collins, Colorado. We had coordinates downloaded from the state oil and gas database and multiple GPS devices, but actually finding the wells proved complicated.

At one site, the supposed GPS coordinates of the well put us directly underneath a giant, five-foot diameter tree. At other sites, the wells were supposedly under roads or driveways or houses. None of them were marked, so it is possible the wells were there. Or maybe they weren’t.

A few years back, Robert Kirkwood, a researcher with the Wyoming Geological Survey, was tasked with locating several hundred active and abandoned oil and gas wells in southwestern Wyoming. He found that a quarter of well locations had been erroneously recorded in the state oil and gas database. Some weren’t even close. The furthest well was more than a mile from its supposed location.

“Some of those were just found fortuitously because we were just walking and walking and then I could see the marker through the sagebrush and I would be like ‘there’s something over there!’ Walk over to it. There it is,” he said.

Others, without markers, he never found. Out in the middle of the Wyoming desert, a few lost wells might not be a big deal, but in other areas, like the Front Range of Colorado, where houses and schools and shopping centers are encroaching on old oil fields, it might pose a bigger problem.

“From public safety perspective, even a slow leak into a building can create an accumulation in the building and then cause an explosion hazard,” said Theresa Watson, an engineering consultant and former energy regulator in the Canadian province of Alberta.

Watson is quick to point out that there is a very, very small risk of an abandoned well causing an explosion, but it does happen. If a well isn’t properly sealed, methane gas can travel up it, and accumulate in confined spaces like say, a basement. Houses built on old wells have exploded as recently as 2007 in Trinidad, Colorado and 2011 in Bradford, Pennsylvania.

“I wouldn’t move because of it I don’t think,” Watson said. “But what I would do is I would probably put a methane monitor in my house.”

Which brings us back to Jeff Parsek. Fort Collins city officials admit publicly that they don’t actually know where the well is that is supposedly under his driveway. It could be where the database shows it is, or it could be under his house, or under the elementary school across the street. The well was drilled and abandoned in 1982, but it wasn’t until 2005 that Colorado started requiring precise GPS locations for active wells.

There is a way to prevent that kind of uncertainty — make developers locate wells before building. That’s what Watson recommended for Alberta, when she was a regulator. Today, the province has a mandatory 5 meter (15 foot) “setback” that keeps buildings away from old wells.

Similar rules are lacking in much of the U.S., even as development continues to encroach on old oil fields. Mark Watson, Wyoming’s oil and gas supervisor, has fielded inquiries this year from landowners in the city of Gillette and even the Campbell County government about building on top of abandoned wells.

“We suggested to them, ‘Hey, it’s probably not a good idea to put your building on top of an abandoned well,’” he said.

But neither the city nor the county has any prohibition on it, so ultimately the judgment call lies with the landowner or developer. The same is true for most municipalities in the region. Broomfield, Colorado is one exception—they’ve had a law in place for 15 years.

“We would require that the developer or the property owner dedicate an easement over the well site, the former well site,” said Anna Bertanzetti, Broomfield’s principal planner. “It has to be at least 50 feet wide by 100 feet long and have access to public roadway.”

The idea is to leave room so that if the well ever leaks and needs to be fixed, a rig can access it. In addition to the dedicated easement, Broomfield requires property owners within 200 feet of the well be notified. With local governments in the region paying so much attention to new oil and gas development, Bertanzetti says it’s common sense to look at the old too.

“I think it’s appropriate,” she said.

And some other places are starting to look at abandoned wells. In 2013, Fort Collins adopted rules requiring a 350 foot buffer between new housing development and old wells. Longmont and Weld County also have buffers of 150 feet and 25 feet, respectively. But none of the rules address development that’s already happened on top of abandoned wells, and none, with the exception of Broomfield, require precisely locating abandoned wells before housing development begins. That patchwork of regulations can mean neighbors are governed by different standards.

One site we visited on our search for abandoned wells was just outside of Fort Collins city limits, in Larimer County—and therefore just outside the reach of the new buffering regulations. The site was unmarked, but to the trained eye it was clearly an old well pad with a big flat area, discernable berms and a nearby access road. If someone didn’t know to ask about abandoned wells, they might find it an enticing spot to build a home. As ill-advised as that might be, in many parts of Colorado and Wyoming, there would be nothing stopping them from doing just that.