Amid a wave of historic coal bankruptcies, states like Texas and Colorado have taken proactive steps to make sure coal companies are on the hook for their future cleanup costs while in Wyoming, over $1 billion of these cleanup costs have gotten tied up in bankruptcy court.

Why are there different outcomes in different energy-rich states?

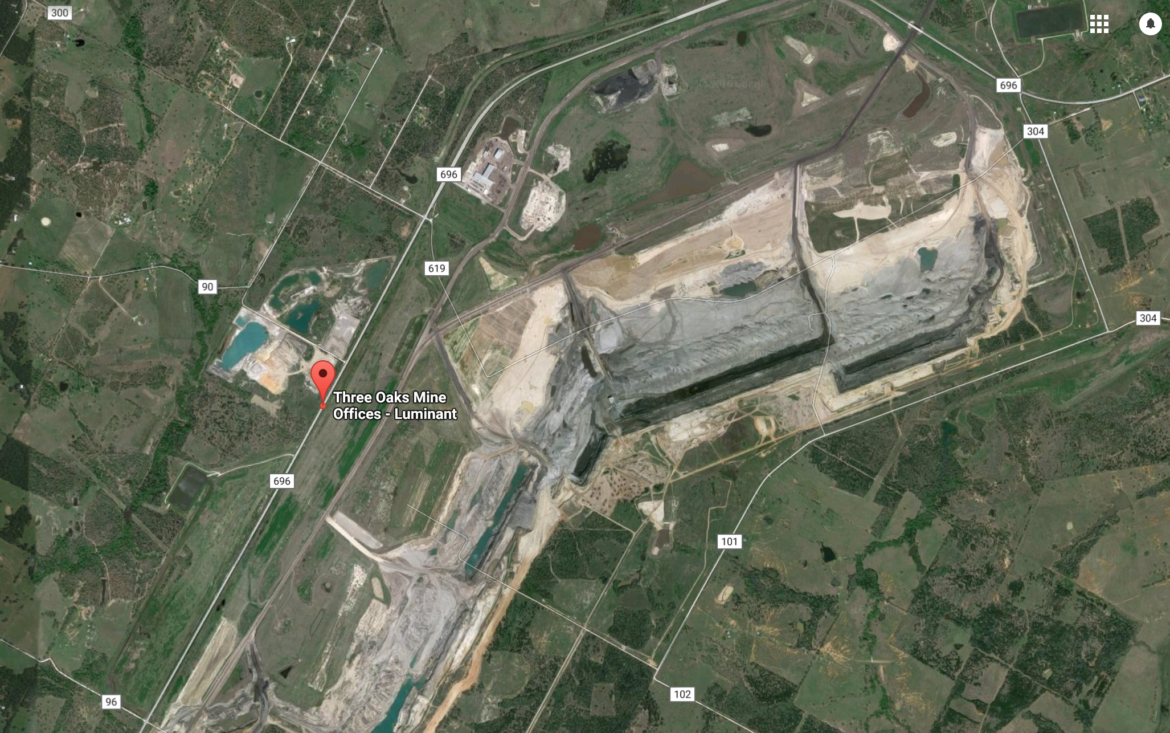

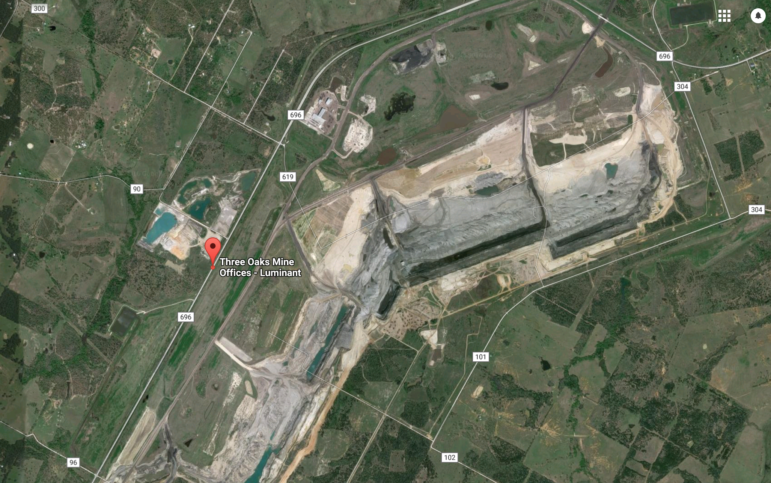

Travis Brown has some ideas. He drives down a quiet country road in Elgin, Texas, a small town about 25 miles east of Austin. A dark, open pit coal mine peeks through the trees. The Three Oaks Mine is owned by Luminant, the largest coal company in Texas, is permitted to operate on nearly 16,000 acres.

“It’s an amazing operation. It’s hard not to be impressed by the technology and what they do here. If you don’t focus so much on the devastation it causes, it’s pretty amazing,” Brown said.

Brown works for the Department of Agriculture but fights coal companies in his spare time, as the head of Neighbors for Neighbors, a community watchdog group. A few years ago, Neighbors for Neighbors along with other environmental groups, like the Sierra Club, started raising red flags about Luminant’s mines, including Three Oaks.

Their concern? That there wouldn’t be funds available for future coal mine clean up if Luminant went bankrupt (which it did). Brown explains:

“In Texas, as in so many states, they had what they called self-bonding. If this operation shut down… all they had was basically a promise from Luminant, that said ‘Oh yea, we’ll clean it up. We’ll promise to do it.’ Obviously, that’s not enough,” Brown said.

Google Earth

Three Oaks Mine is permitted to operate on nearly 16,000 acres.

A self-bond is backed by a company’s financial strength, not real money. In 2014, Luminant had over $1 billion in future cleanup costs, held in self-bonds.

On April 29th of that year, Luminant’s parent company, Energy Future Holdings and 70 affiliated companies, did indeed file for bankruptcy. The company is still working through that process. On May 16th, Luminant asked regulators to approve replacement bonds. In June 17th, regulators approved the plan for Luminant to replace the total value of its self-bonds with a collateral bond. That bond is backed by its parent company’s assets and would be one of the first debts to be paid back.

That is exactly what is supposed to happen.

The state of Colorado and Peabody Energy made a similar, much smaller deal in April of this year. But it hasn’t happened anywhere else on the same scale.

So why did it work in Texas? Travis Brown, and other environmental advocates I talked to have a theory. Brown thinks this situation was a political liability for Texas regulators.

“They were afraid the taxpayer would be left with footing the bill to clean it up and they would be the guys who would get the blame for letting that happen,” Brown said.

But according to the regulators themselves- the Texas Railroad Commission- they were just following the rules. In an emailed statement, RRC spokesperson Ramona Nye wrote:

“Railroad Commission rules are clear on self-bonding qualifications. If a company cannot meet the requirements for self-bonding, that company must provide another form of acceptable financial assurance under our regulations.”

Then, there is the issue of timing. The commission had time to resolve the self-bonding situation with Luminant before bankruptcy.

“Luminant was very upfront with the Railroad Commission early on, where that may have not happened in other states, with other companies,” explained Ches Blevins, Executive Director of the Texas Mining And Reclamation Association.

In other states, like Wyoming, self-bonding and bankruptcy have unravelled very differently.

Right now, Wyoming has over $1 billion in self-bonds held by two bankrupt coal companies, Peabody Energy and Arch Coal.

Why doesn’t the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality have full replacement bonds in hand? Well, a lot of reasons, they say. Regulators didn’t always have the most recent financial information leading up to bankruptcy. In some cases, once the companies actually filed for bankruptcy, regulators say their hands were tied by the court.

One self-bonded coal producer, Alpha Natural Resources, emerged from bankruptcy in July. The company’s Wyoming assets are now part of Contura, a new company. The plan is for Contura to first provide “acceptable reclamation bonding instruments,” before Alpha’s mining permits are transferred. Under a settlement between Alpha and Department of the Interior, resolved in July, Contura will not be allowed to self-bond.

The bottom line is that Wyoming wants these companies to stay in business.

“There are a lot of ways, as a regulator, that you can accomplish your mission. So you have rules and regulations in place, you can apply those in a way…I think we have a responsibility as public officials to do that in the most reasonable way,” Todd Parfitt, Director of the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality said. “If you can get to the same end point and achieve the same goal then you ought to do that in a way that allows the mines or the industry to continue to operate and continue to keep people employed. Why wouldn’t you?”

But Parfitt was not willing to go further and say that he is confident taxpayers won’t have to foot the bill for any of this reclamation in the future. “There’s always going to be risk, with everything that we do,” he explained.

The federal government announced plans this week to tighten its mine reclamation rules, making it harder to self-bond cleanup obligations. Joe Pizarchik, the director of the Office Of Surface Mining Reclamation And Enforcement, explained why:

“This is a turbulent time. A time where there are transformations going on in the mining and energy industry in the United States. This is also a time to act because we now know that our self-bonding rules do not work,” Pizarchik said.

What’s Next:

- Check out Inside Energy’s Coal Watch 2016 for the latest developments

- Reid Frazier reports that Appalachia has been dealing with mine cleanup for decades

- How does coal mine reclamation actually work? Stephanie Joyce digs in.