Oil and water don’t mix, they say, but when it comes to drilling an oil and gas well, water is a big part of the process.

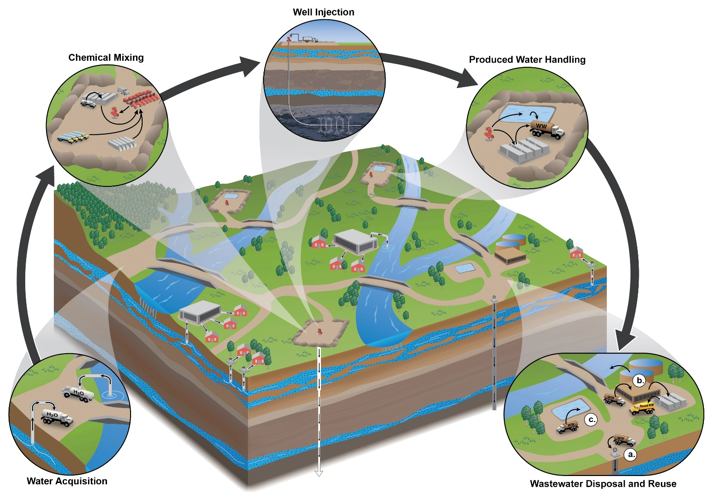

Each day, 2.4 billion gallons of wastewater pour out of U.S. oil and gas wells according to 2009 estimates from Argonne National Lab. This includes water pumped down for fracking and water that flows up to the surface from deep aquifers. Both contain dissolved minerals and chemicals including many that are harmful, and both can have impacts on drinking water resources if not handled with care, according to a 2015 report from the EPA.

The water coming up from deep underground, called “produced water,” contains salt and other dissolved minerals, hydrocarbons, and sometimes radioactive elements. It acquires these components naturally, from its time holed up within rocks. In Colorado, produced water is nearly as salty as the ocean, but that varies by geography. The produced water coming out of wells in Pennsylvania and Ohio, for instance, can be ten times as salty as ocean water.

The water used for fracking – a mixture of water, sand, and chemicals – is pumped underground at high pressure and wedges rocks apart. The sand stays put in the cracks, creating pathways for oil and gas to travel towards the well, and about 40% of the water and chemicals flow back to the surface. Some of the chemicals in fracking fluid are not harmful. Others are toxic. Most are present in very small quantities, but even in tiny amounts chemicals like benzene are dangerous. (Check out FracFocus.org to learn about chemicals used in fracking fluids. The database lists ingredients used on over 100,000 U.S. fracking jobs from states that require disclosure.)

Francisco Reyes / U.S.G.S.

A bottle of oil and produced water collected from a well in Texas

Joseph Ryan and Jessica Rogers, researchers at University of Colorado, recently identified that, of the hundreds of chemical compounds used in fracking fluid, fifteen often-used chemicals are of particular concern because they are both toxic and able to stick around in the environment for a long time.

Fracking fluid and produced water gets mixed together. In the U.S., nearly all of this wastewater is injected into disposal wells. These deep wells are designed to prevent the water from escaping and contaminating drinking water aquifers, surface water, and ecosystems. In eastern Colorado, disposal wells are drilled to about 9000 feet deep. That’s 2000 feet below the rocks that contain oil and gas and it’s very unlikely that the wastewater will get into drinking water once pumped into the disposal well. However, in cases where disposal wells that are not well designed or drilled due to lax rules, that might not be the case.

There is another concern about the safety of disposal wells. They are the cause of most of the earthquakes associated with oil and gas development. If the water, under pressure, gets into an existing fault deep underground, it can cause an earthquake. This has caused Oklahoma to become the most earthquake-prone state in the country in recent years.

Also, quarantining water in disposal wells means that it is taken out of the water cycle. Less water is available to move from clouds to lakes, rivers, groundwater, and the ocean and then back to clouds. Using a resource in a way that can’t be replenished is not sustainable in the long term, so taking water out of circulation is not ideal.

To cut down on the amount of disposal wells and the amount of water taken out of the water cycle, wastewater from oil and gas development can be treated and then reused for fracking other wells.

Typical water treatment plants, like the type that you’ll find filtering a city’s water supply, weren’t designed to deal with wastewater from oil and gas development. “This water is way more complex because it not only has organics but also has lots of salt,” said James Rosenblum, postdoctoral fellow at University of Colorado.

Researchers are searching for other methods to clean salt and toxic components from the water. Rosenblum is part of a team testing and comparing methods for cleaning up wastewater from oil and gas development. They are using microbes to break down toxic chemicals like benzene and testing special membranes that have a mesh so small that water molecules can get through and larger molecules cannot. These methods might get the water clean enough to drink, but it’s more likely that the cleaned water will be reused in oil and gas development.

Today, very little wastewater in Colorado is treated and reused by the oil and gas industry. Most is used once and then injected into a disposal well. In places where disposal wells are not available, like Pennsylvania, reuse of water is common.

“The industry recognizes this as an issue,” said Rosenblum. It’s economics. Reusing water can be less expensive. A group of experts organized by the Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin also came to the conclusion that treating and reusing water in the industry is the most economic option. You don’t have to buy it, truck it around, and then dispose of it if you can clean it and use it again.

This story was made possible by a collaboration between Inside Energy and AirWaterGas, a Sustainability Research Network funded by the National Science Foundation.