While working on a story on solar energy and its impact on the electric grid, I came across the term “combined heat and power,” or CHP.

I had never really heard of it before, yet it is widely used in the energy industry. And that prompted the deeply existential question:

What is combined heat and power?

It’s pretty much how it sounds: CHP refers to the use of excess heat from heating sources, such as boilers, to generate electricity by spinning turbines. Or, the other way around—using the extra heat from producing electricity at power plants to provide needed heating or even cooling in those plants.

According to the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory:

“While the the traditional method of separately producing usable heat and power has a typical combined efficiency of 45 percent, CHP systems can operate at efficiency levels as high as 80 percent.”

It’s not a single technology, but a whole quiver of devices and layouts and strategies used to increase that efficiency.

According to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, back in the 1970s the technology only really made sense on the scale of 50 MW, which is huge. So pretty much only major factories with big, giant boilers put in these combined heat and power systems.

But, in recent years, these systems have advanced to be cost effective for heaters 100 to 1,000 times smaller. It’s being used on college campuses, in hospitals and commercial buildings and even in individual households.

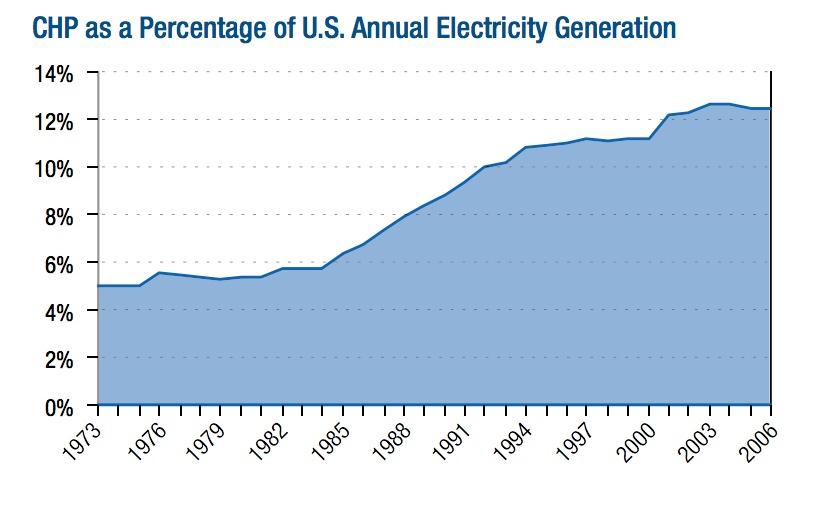

What shocked me is how big of a deal this co-generation stuff has become.

CHP projects provided about 12 percent of US electricity as of 2006, “more than the output of all the wind, solar, biomass and geothermal resources combined.”

Whoah.

And I had never really heard of it.

The Oak Ridge Lab says unfamiliarity with CHP is actually one of its biggest barriers to wider implementation. They say if the US were able to boost CHP to producing 20 percent of the nation’s electricity, it would be the equivalent to removing more than 154 million cars, or more than half the US vehicle fleet, from the road.

“…achieving that environmental impact would be a huge accomplishment, and few other technologies or practices can be implemented as economically or quickly as CHP.”

But widespread adoption of this kind of technology, or rooftop solar for that matter, could one day disrupt the nation’s current model of providing electricity through traditional utilities connecting Americans to large-scale, industrial power plants.

Inside Energy will be exploring this idea in the coming weeks.