For Colorado School of Mines petroleum engineering professor Carrie McClelland, teaching a seminar of 45 students seems like a bit of relief. Normally her class sizes are closer to 80 or 90.

“It makes it difficult to make sure that they’re still getting a great education,” she said.

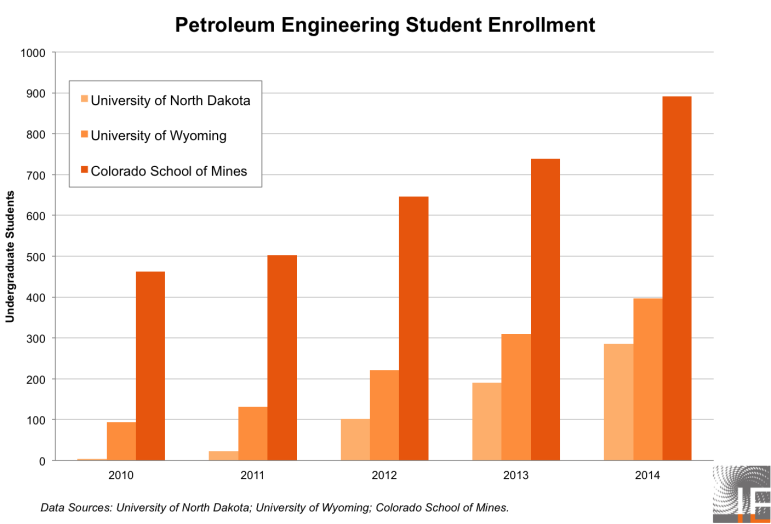

Enrollment in petroleum engineering at the school of mines, and at similar programs around the country has risen dramatically in the last five years in response to the nation’s energy boom.

Dan Boyce

Where enrollment at the Colorado School of Mines nearly doubled in the past five years, the University of Wyoming more than quadrupled in that time. UND’s program exploded from four students in 2010 to 286 this semester. See the data used to make this chart here.

Students are flooding into these programs to cash in on high-paying, industry jobs. Conveniently for the students, there are plenty of these jobs to go around.

It has not been convenient for many educators. Although the School of Mines has gone from under 300 undergraduate PE students to about 900 in the last decade, the faculty has stayed the same size.

“It’s becoming unmanageable in some sense,” said University of Wyoming professor Vladimir Alvarado.

His program has quadrupled in the last five years. They are requesting more faculty to handle the growth, but the problem is finding qualified professors. Public universities just can’t compete with the salaries being offered by oil and gas companies.

At the Colorado School of Mines, a petroleum engineering professor makes a little more $100-thousand a year, on average. They could make double if they went into industry.

Schools are doing what they can to manage; creating more and more sections of the most popular classes to reduce class sizes and moving to more multiple choice tests to lower grading time. The School of Mines is having more undergraduates work as Teachers Assistants, like Senior Kate Denninger.

“It’s great to be on the opposite side of things,” Denninger said, “trying to help these guys get through the same problems I did.”

Industry is stepping in, too, helping pay for new equipment and classrooms. At the School of Mines, oil company Schlumberger is even paying for one of its own employees to teach courses as an adjunct professor. Also, interim department head Erdal Ozkan said a saving grace in the professor shortage has been foreigners. More international academics are willing to accept lower pay for a chance to work in the U.S, and particularly, Ozkan says, for U.S. universities:

“We have the best universities, we still have the best research programs, we have the best connection with the industry,” Ozkan said.

Professor Carrie McClelland—she won’t be contributing to the teacher shortage either. She actually took the opposite path, coming into the classroom from industry.

“Yeah, it’s not about the money for me,” she said, even if that is what it’s about for a lot of her students.

What’s Next:

- There are 21 petroleum engineering programs in the country. This site ranks the top 15 PE schools for this year.

- USA Today recently ranked the top-10 highest paying college majors. Surprise surprise, petroleum engineering is number one.

- The hiring problems faced by academic institutions are also being faced by state regulators trying to hire specialists in oil and gas. Check out this story from our own Stephanie Joyce.