It’s old news by now that oil had a bad week, dropping to its lowest price in years. Much of the attention was on the consumer side: A simultaneous drop in gasoline prices. But in oil-producing states like North Dakota and Wyoming, falling prices have bigger implications — and could cause bigger headaches down the line.

As Inside Energy’s Emily Guerin reported this week, North Dakota’s Department of Mineral Resources hosts a press conference every month to discuss the latest oil production figures. It’s called the “Director’s Cut” and it’s normally a pretty low-key affair: Local reporters show up and banter with agency director Lynn Helms, while reporters from the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Reuters log on via the Internet. At exactly 1:30 p.m., the webcam clicks on and the whole thing goes live.

Helms started the report this week as usual, noting that oil production in North Dakota is on the rise and more wells are being drilled. But all anyone really wanted to talk about was this: what’s going to happen to North Dakota now that crude oil prices are tanking?

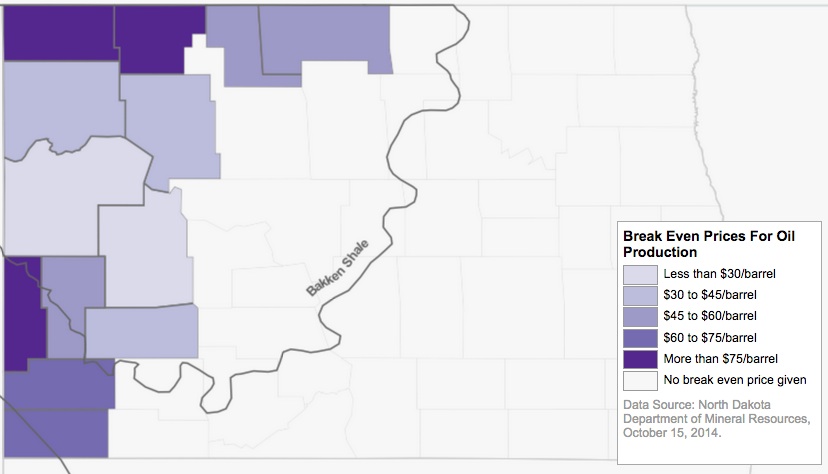

“We’ve taken a look at the break-even oil price on a county-by-county basis and we have three counties that right now, at less than $70/barrel, are below break-even,” Helms said.

Three North Dakotas counties where it’s not profitable to drill anymore. How big of a deal is that?

“We’re talking less than a ten percent impact [on state rig counts],” he said. “But still, if it’s your county, it’s a significant impact.”

That’s because fewer rigs means fewer drilling jobs, fewer loads of gravel to buy, and fewer miles of road to build in those places. The impact goes beyond those counties though–it also hits the budget office in the state capitol, Bismarck. When North Dakota’s budget planners came up with their preliminary revenue estimates, they were banking on prices staying at $90 per barrel. Now, they’ve convened a Halloween meeting to reconsider.

“I am quite positive there will be a revision, looking at what oil prices are today — and hopefully that two week period will give us a sense of the trend, whether we’ve reached the bottom or we’re continuing to go down,” Helms said.

Of course, North Dakota isn’t the only place where low oil prices mean budget troubles. In fact, the very people who have the most control over the global price of oil — members of the OPEC cartel — also depend on high oil prices to fund their governments. But the group’s most powerful country, Saudi Arabia, has signaled it is willing to live with low prices if it means hanging onto market share. US shale oil is one of the targets.

“The global markets don’t know how to respond to something that’s brand spanking new,” says Niles Hushka, CEO of KLJ, the consulting firm that studied break-even prices for North Dakota. “That’s shale oil.”

The United States has produced more oil in recent years than anyone ever anticipated would be possible. That’s part of the reason for the current glut — and the falling prices. But for now, no one on the ground in oil-producing states is making huge changes to their drilling and production plans.

“I think what we’re seeing right now is an industry that can’t quite figure out what’s happening,” Hushka said. “So, the industry doesn’t want to overreact.”

Wyoming State Geologist Tom Drean is not overreacting.

“There’s been a long history of oil prices going up and going down,” he said, when asked for his thoughts on the week’s news.

Wyoming doesn’t produce nearly as much oil as North Dakota, and it doesn’t have a detailed analysis of break-even prices like North Dakota, but Drean says so long as prices stay above $80 a barrel, there probably won’t be any big changes in drilling activity. Even below $80 a barrel, he says the state’s emerging oil boom isn’t likely to bust.

“I think it’s safe to say it’ll be a slower ramp up than it would be if the price of oil was $100 a barrel. [But] it’s difficult at this stage to say what the exact impact would be,” Drean said.

The state’s budget forecasting group — of which Drean is part — will have to make some predictions about the future in coming days though. The Consensus Revenue Estimating Group is supposed to present its initial analysis in the next week of how much money will be available in the coming year for funding things like schools and roads at a Legislative committee. With few indications of oil prices stabilizing, all signs point to that being an extremely difficult task.