When Richard Kail retired to the northwestern Wyoming town of Pinedale in the late 1990s, it was a sleepy place mostly getting by on jobs in tourism and government. Kail bought some apartments and a hotel in Big Piney, about thirty miles south of Pinedale. He did steady business — nothing special. That is, until around 2005, when he started to get a lot more calls.

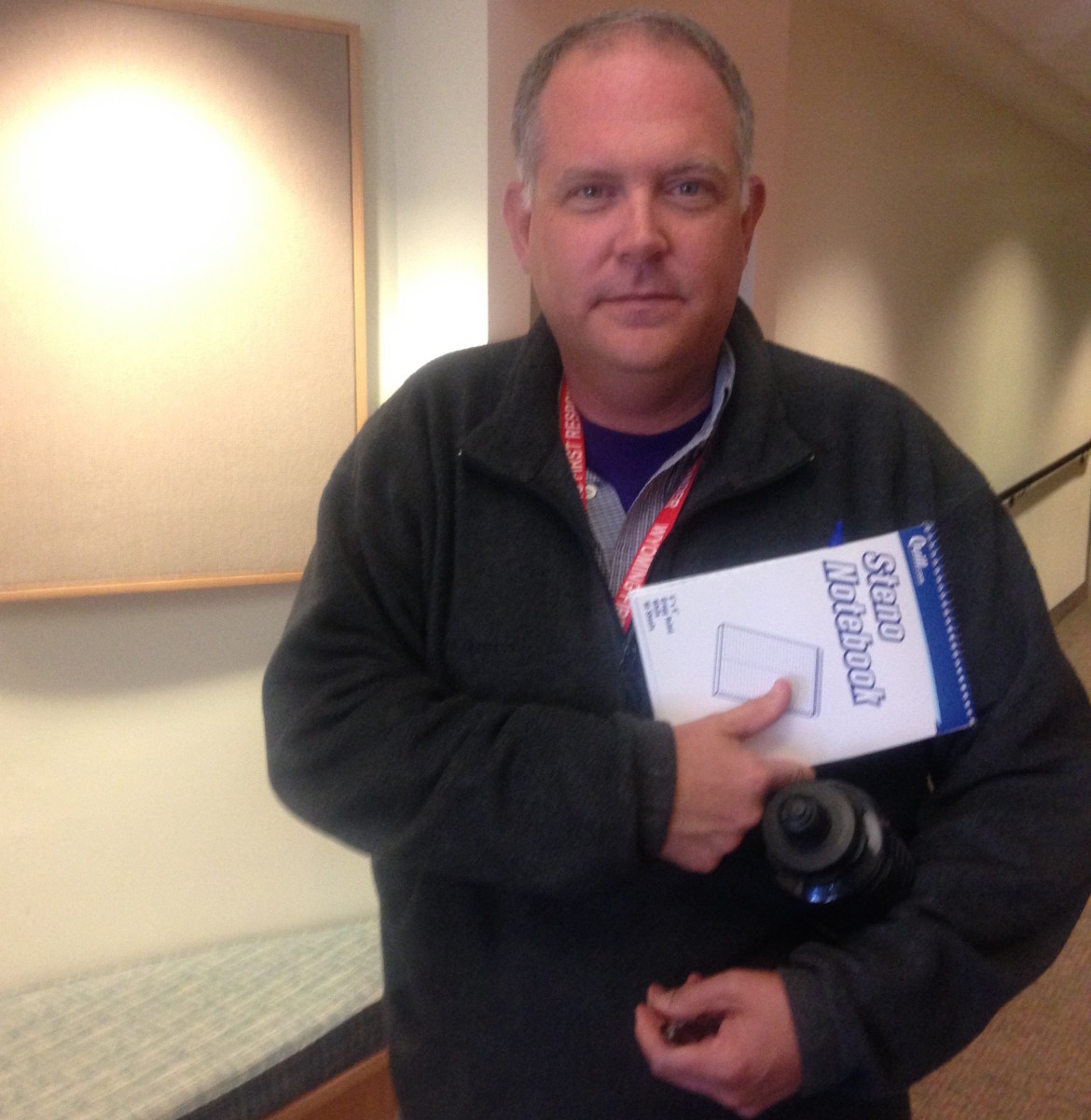

Miles Bryan / Wyoming Public Radio

Steve Smith is the former mayor of Pinedale, a town in western Wyoming.

By the mid-2000s, hydraulic fracturing had opened up thousands of natural gas wells around Pinedale. Hundreds of energy workers descended upon the area — all looking for a place to stay.

“There were continually calls,” Kail told me in his Pinedale home. “They were willing to pay just about anything you ask them for [a room]. There was a real frenzy for finding places.” The demand for housing was just too much for the area to handle, said Steve Smith, mayor of Pinedale from 2006 until last June. “At the end of the day we just couldn’t pull it together here.”

Pinedale scrambled to react to the boom, but there was never enough housing as their were energy workers searching for a place to stay. What got in the way? First, the free market. Smith says,

“Everything was going up and up in Pinedale. Folks that had lived here for a long time were seeing houses that might have been valued at 100 to 150 thousand dollars now selling for 300 thousand dollars. In that real estate market it’s very difficult to find land to put in attainable housing.”

“Attainable housing” — that is, housing that is not necessarily cheap, but is available.

The second issue is the sewer lines and roads and stoplights: all the stuff a town has to build along with housing. “Previous administrations had long-term plans to improve infrastructure. But when you have this many new people coming, and this much new traffic on your roads…it took us some time to crawl out from behind that eight ball.”

The third big issue, which was more of a question for Pinedale, is a little more abstract: Do you make the energy workers a part of the town; a part of the community? For Mayor Smith, the answer was yes. “I wanted those people coming into our community to be part of our community,” Smith said. “To pay sales tax and property tax and enroll their kids in school. I thought that was important, and I still do.”

Smith says locals welcomed the idea of their bars and diners filling up with energy workers. But when it came to housing, he was overruled. A housing report commissioned by the town in 2008 recommended it limit new residential development to cushion the real estate values of long-term residents. And that is pretty much what happened — ultimately very little worker housing was built.

Fast-forward four years and the same scenario is playing out again, this time in the Northeast Wyoming town of Wright. Roger Jones has developed apartments and townhouses in energy towns in Wyoming and the Dakotas. Right now, he’s building some apartments in Wright, which is currently seeing a surge in oil development. These construction projects take an average of 1-2 years, so contractors often underbuild because they don’t know how long the boom will last. “You always want to have a waiting list,” Jones tells me by phone. He says he was optimistic about the Wright project a few months ago, but the sharp drop in the price of oil recently has him concerned.

Unlike the boom in Pinedale — the sheer size of which caught everybody off guard — Wright has had plenty of lead time to track the growth of oil and gas work. Mayor Tim Albin says he wants to see the energy workers in the area living, and shopping, in Wright, but he says the town has to invest in the long-term first. So far, that has meant using oil tax proceeds to build an almost 10 million dollar recreation center…but taking it slow with housing. Albin says,

“We want to build for the future and have our town be a permanent structure. We’re not trying to just build stuff to handle the overflow and then go ‘we don’t care what happens in two years whether it folds or not.’”

When small towns in energy states are hit with a boom, they know a bust is probably coming too. Even with plenty of foresight, it’s hard to get around the fact that investing in the needs of energy workers might not be a good investment for the town.

“I mean this happens, everyplace,” said Pinedale innkeeper Richard Kail. “Nobody is prepared. Those things just happen and they adjust and — it’s a bitch.”