Stephanie Joyce

In Vladimir Alvarado\’s petroleum engineering class, there are no signs enrollment is shrinking, although job prospects are getting slim.

A year ago, a petroleum engineering degree seemed like the ticket to a bright and well-paid future. With six-figure starting salaries for a bachelor’s degree and endless optimism about the shale revolution, enrollment climbed rapidly in petroleum engineering programs across the country. But now that the oil price slide has turned to an oil price slump, the luster is wearing off.

When Evan Lowry first enrolled at the University of Wyoming, his plan was to be a chemical engineer, like his dad, but the oil industry was booming and he quickly changed his mind.

“[I] switched just based off of the outlook for petroleum engineers,” he said.

An outlook that included not only exceptional compensation, but also near-certainty of finding a job. When I spoke with him last April for a story about a shortage of petroleum engineers in regulatory jobs, he said that he wouldn’t consider working for the government.

“As far as the salary goes, it’s kind of hard to go with something like that when there are so many other opportunities in the industry,” Lowry said.

Today, with oil prices at half what they were in June and companies laying off hundreds of thousands of people, his perspective has changed.

“Currently I’m just applying to any job that’s open,” he said. “I think I’m at 35 or 36 right now.”

He’s also back where he started: He’s enrolling in a chemical engineering master’s degree — just in case none of those petroleum engineering jobs pan out. He isn’t the only one. At the Colorado School of Mines, Professor Carrie McClelland says plenty of her students are in the same boat. Every fall she invites a guest speaker to her class, and he always opens with a question about how many students have jobs lined up after graduation.

“Usually 75 to 80 percent of the people would raise their hand, but we maybe had 10 or 15 students raise their hand this year,” she said.

McClelland adds that some seniors have had offers rescinded and plenty of students are suddenly considering graduate school. But oil prices aren’t the only problem — she says there are just too many students these days pursuing petroleum engineering degrees.

“I think the demand has already leveled off even though the number of students continues to increase, and we’re going to see a lot of students that end up with a petroleum engineering degree but have to go find a job in a different industry,” she said.

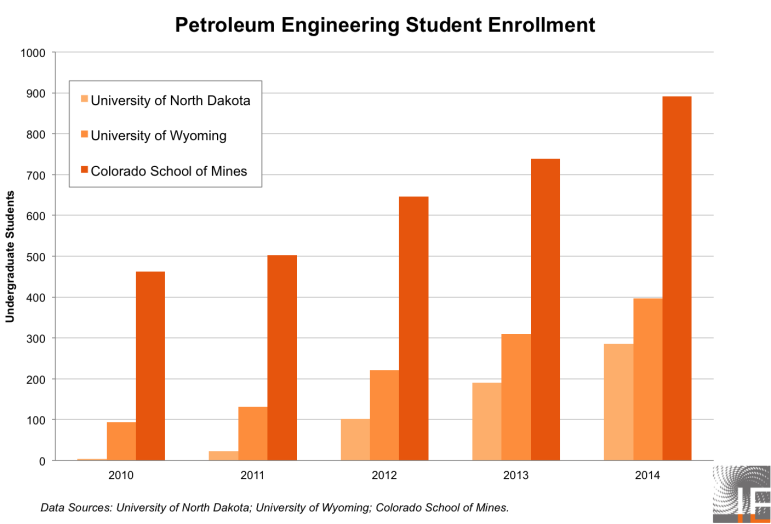

The School of Mines has seen enrollment double since 2010, while the University of Wyoming and the University of North Dakota have seen even larger increases.

“We won’t see the impact [of falling oil prices] just yet, simply because there is inertia in the market,” said Vladimir Alvarado, head of Wyoming’s petroleum engineering department. “It won’t stop all of a sudden.”

Stephanie Joyce

Vladimir Alvarado is the head of the University of Wyoming\’s petroleum engineering department.

And he doesn’t want it to — although he would like to see it slow. Class sizes in recent years have overwhelmed the University’s teaching staff and put a huge strain on department resources. In light of that, Alvarado thinks low oil prices may be a good thing.

“It will give us time to catch our breath, and improve the quality of what we do,” he said.

But what Alvarado doesn’t want is a repeat of the 1980s. In the early part of that decade, students also flocked to petroleum engineering programs amid high oil prices, and then cleared out just as suddenly when the industry busted. The University of Wyoming ended up shutting down the entire program — something that clearly is on Alvarado’s mind these days.

“If we are clever, we can sustain healthy activity even with fewer students, even if it goes down like before. We need to avoid panicking about this and shutting down programs,” he said. “It is very expensive to restart a program.”

Oil prices would have to stay low for years for anyone to seriously talk about shutting things down, but as with many things oil — whether it be a drilling frenzy or an enrollment surge — it may prove difficult to strike a balance between the extremes.