Emily Guerin

Christine Peterson points at an aerial photo of a wastewater spill near her land in Bottineau County, North Dakota.

The North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources criticized certain aspects of our story on North Dakota’s oilfield spill problem. After going through their corrections, we made two small changes to our story (scroll down to see the update at the bottom). Below are their critiques, with our responses.

1. Bottineau County wastewater spill

Our story: “Abruptly the green quilt of soybeans and wheat ends. We look out over a vast expanse of puddles and bare soil caked white.”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: The puddles are not saltwater. North Dakota has a limited, three month window where reclamation is possible. We have recently experienced two very wet years, making reclamation of the bare soil very difficult.

Our response: We didn’t intend to imply that the puddles were saltwater. The point of the description was to show how the impacts of this particular spill are on-going and have taken farmland out of production.

“Peterson, who is suing some of the companies responsible for spills on his land, believes the underreporting has contributed to the slow pace of clean-up and lack of media coverage of the spill.”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: North Dakota’s climate has contributed to the slow pace of clean-up. Reclamation can only be done for roughly a three-month period, and the last two years have been very wet cycles which also limits when reclamation can be performed.

Our response: The Department of Mineral Resources is critiquing Peterson’s opinion. There are many factors that contribute to how quickly a spill can be cleaned up, and the landowner and the Department may disagree about the pace. Department of Mineral resources’ director Lynn Helms readily admits that final spill reports need to have an accurate spill volume: “We work with them very hard to make sure the final spill report has an accurate volume because it’s going to dictate how well the cleanup process went and if any additional clean up or monitoring or measurement needs to take place.”

“But another document from the state Department of Health shows the company later hauled off 2 million gallons of wastewater, making it one of the largest spills in state history. The official spill estimate has not been updated.”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: Two million gallons would include rain, snowmelt and saltwater.

Our response: According to the Department of Health document, “Petro Harvester had removed 52,861 barrels (2.2 million gallons) of water from the heavily contaminated ponds. In addition to the professional survey and analytical results, this strongly suggests that the release volume far exceeded 300 barrels of oilfield brine.”

Some of what the company removed from those ponds was likely rain and snowmelt – but that is exactly what makes wastewater spills so difficult to remediate. Wastewater mixes with fresh water in creeks and ponds and seeps into underground aquifers. In its efforts to clean up January’s three million gallon wastewater spill, for example, Meadowlark Midstream acknowledges that “a significant amount” of what it pumped from Blacktail Creek is fresh water. It is impossible to separate the two.

2. Characterization of spill problem by state officials

In January 2013, Director Lynn Helms testified in front of the state legislature against a bill to require monitors on all wastewater pipelines, saying the proposal was too broad and that the monitors would not be effective in catching the smallest leaks.

“Yes, the number of spills is up,” he said. “But look at it in comparison to the number of wells. The rate of spills is way, way down.”

In fact, using the state’s own data, we calculated that the rate of spills was way, way, up. It’s more than twice as high as it was in 2006, at the start of the Bakken boom, and three times as high as in 2004.

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: In January 2013, when Director Helms testified, he would have presented data through November 2012, the most current month for which data would have been available. At that time, the rate of spills per well was down from 2011. Even when looking at the graph within the Inside Energy report, the slope of the lines is on different paths, with wells increasing much more dramatically than spills.

Our response: Our statement, “In fact, the rate of spills was way, way up … It’s more than twice as high as it was in 2006,” was referring to the 2014 recent spill rate of 0.17 spills per well. We should have cited 2012 statistics when critiquing Helms’ 2013 statement and have made that change in the story.

However, our assertion that the spill rate is up still holds for 2012 data. In 2012, the spill rate per well was 63 percent higher than in 2006, according to state data.

The Department of Mineral Resources says that Helms was correct in saying the rate was “way, way down” because the rate of spills decreased 13 percent from 2011 to 2012. But Helms presented this one-year decrease as the overall trend, when in fact, the spill rate had risen substantially since earlier in the boom, and continued to rise after his comments. When we asked Department of Mineral Resources spokeswoman Alison Ritter why Helms did that, she wrote, “he never indicated he was talking about trends. He simply mentioned spills were down.”

Finally, the Department of Mineral Resources says that “even when looking at the graph within the Inside Energy report, the slope of the lines is on different paths, with wells increasing much more dramatically than spills.”

This statement is misleading. As oil production grows, we should expect to see increases in both the number of wells and spills. What we wanted to know is: Have spills increased disproportionately as the boom has progressed?

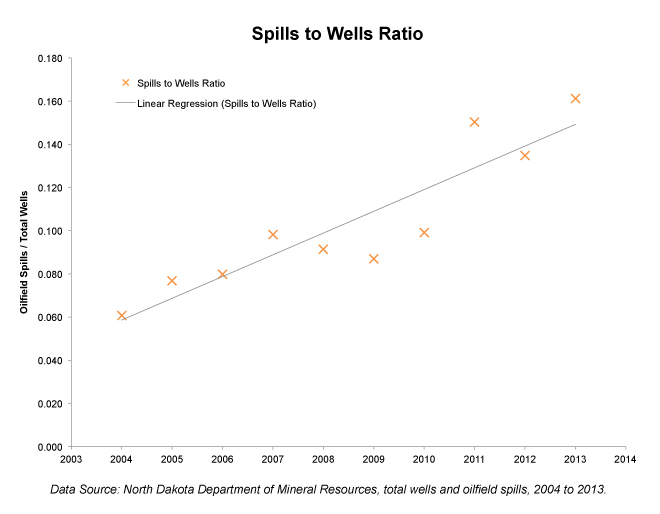

To answer this question, we looked at the spill to well ratio, or spill rate, calculated as number of oilfield spills divided by total wells:

Jordan Wirfs-Brock / Inside Energy

This graph shows the spills to wells ratio for each year. The black line is a linear regression showing the long-term trend. View the data used to make this graph.

The trend line on this chart shows that the spill rate has been increasing over time. The rate increased more in some years than in others, and even dropped in some years (2008 to 2009, and 2011 to 2012); but the overall trend is that the spills are increasing proportionately faster than wells.

Here are some other things we know about how spills and wells have changed relative to each other over time:

- From 2004 to 2013, wells in North Dakota increased 180 percent and spills increased 644 percent.

- In 2004, there was one spill for every 16.5 wells; in 2013, there was one spill for every 6.2 wells.

3. Regulators’ relationship with industry

“But as for the coziness with industry, people have been complaining about that for a long time. Here, promotion and regulation go hand in hand. At a recent meeting in the statehouse, Helms wore a yellow silk tie he got at an industry conference. It’s embroidered with little pumpjacks and the words ‘Bakken Strong.’”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: Lynn received the tie as a gift for speaking on a regulatory panel at the Williston Basin Petroleum conference. The panel included regulators from Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Montana, and South Dakota. This is an event that is co-sponsored by the Department of Mineral Resources, Saskatchewan Ministry of Energy Resources and the Petroleum Technology Research Centre. The conference is vital to North Dakota Geologic Survey because it is used as a data sharing opportunity with researchers from across the Williston Basin into Canada. This fact was presented during testimony from State Geologist Ed Murphy on Senate Bill 2374. It’s the Geologic Survey that has role of promoting our state’s resources and this conference is a huge part of that.

Our response: The Department of Mineral Resources is not alleging any factual error in the story.

4. Spill reporting

“Inaccurate report volumes don’t appear be a priority for inspectors like Kris Roberts at the Department of Health.”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: Reports are not inaccurate. They are estimates. What at the time of the spill, it is more important to understand what spilled, if it contained within dikes of the well pad and then volume estimates to determine clean-up procedure. Lastly, what was the root cause of the spill?

Our response: Nowhere on the Environmental Incident Reports does it say that spill volumes are an estimate. Nor does the report indicate the volume could be updated in the future. And if that volume is updated in a final report (oftentimes years later), it is not updated in the Department of Health’s public database. There is no way to know if there is a new, more accurate, estimate—except to ask. Compare that to Colorado, which maintains one spreadsheet with the most up-to-date information on all spills.

“To see [the final reports], one would either have to pay $50 for an annual subscription to the state’s oil and gas division website or go in person to the Department of Mineral Resources office in Bismarck.”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: Or, they can ask for it. As public information officer I [Alison Ritter] have filled requests from individuals who are looking for reports or follow-up information from spills that have occurred on their land. I have never had an individual, representing only themselves, request information relating to all spills that occurred over a certain time period. Spills are very site specific and the information should be filed that way as well.

Our response: We acknowledge that one could ask for a spill report in addition to the other ways we listed and have made that change in the story. However there is no public list of spills with final spill reports, nor are final spill reports presented alongside the initial ones in the Department of Health’s online database.

“In early February, Republican Rich Wardner, Senate Majority Leader, testified in favor of a bill to beef up pipeline monitoring and inspections. He said he’d like an independent inspector to do the job because he didn’t trust the state. “I’ve just about had it up to my eyeballs with people taking care of their own,” he said. “When you have the fox guarding the henhouse, it’s not very good.”

Department of Mineral Resources complaint: Wardner did not understand (Triplett’s) question correctly. That is how he answered, but it is not what he meant. As we discussed it with him immediately following the hearing. I [Alison Ritter] even went to his office the next day to be sure.

Our response: Here is the full transcript of that portion of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee hearing on Senate Bill 2374 from February 5, 2015:

Senator Connie Triplett: Senator Wardner, you made a comment regarding the word inspection of the pipeline and you said we’ll have to figure out who’s going to do the inspections. I guess the choices are: a company agencies. Do you have an opinion on which direction we’re going or what was intended by this?

Senator Richard Wardner: The way things are going, I guess I’m for an independent contractor coming in and inspecting those pipelines. I know it’s going to cost more, but I, and this is in a lot of areas in state government, I have just about had it up to my eyeballs and people taking care of their own. And when you have the fox guarding the henhouse it’s not very good. can have its own internal inspectors do it and file a certificate saying they’ve done it, or we can hire additional inspectors for our regulatory

This comment was interpreted by myself and initially by others, including Department of Mineral Resources Director Lynn Helms (according to Wardner), to mean Wardner didn’t trust the state to inspect pipelines. Wardner now says he was referring to companies inspecting their own pipelines and said he was OK with state inspectors doing the job.