To get to Colorado’s North Fork Valley, you drive along the area’s namesake, the North Fork of the Gunnison River, past stands of aspen and cliff bands. You round a corner and suddenly you’re literally driving through a coal mine. There’s two-story high piles of black coal and conveyor belts that stretch over the road. There’s two more mines down the river, and then you’re in a gorgeous green valley filled with orchards and ranches.

Colorado doesn’t have the same strong associations with coal mining as Wyoming or West Virginia, but the industry has formed the bedrock of many small town economies on the Western Slope. Like many other coal regions, production is way down here and the area is changing.

I met Rene Atchley at her office on the campus of Energy Tech, the branch of the county school district that organizes mine safety training classes. She’s organizes these classes and has been around coal all her life, like almost everyone in her family: husband, son, stepchildren, father. She likes to remind people that “every time [a train] goes out of here with a load of coal, someone’s getting a paycheck.”

But now, there’s about half as many trains as there used to be. And recently, three of her family members were laid off from two of the Valley’s three coal mines.

“I think the writing is on the wall that you’re not going to retire out of the coal industry anywhere, whether it’s a power plant or a coal mine,” she said.

Coal production in the North Fork Valley has fallen about 90 percent since early 2008, according to Energy Information Administration data. This area has been through booms and busts before, but this one feels different.

“It’s a dying industry,” said Cliff Brewer, who worked at the Elk Creek coal mine in the Valley for 14 years before being laid off in 2014, along with about 300 other miners.

“I don’t have a college degree, I make $80,000 a year,” he said. “You tell me another job I can get that’s going to pay me [that much]. There’s none.”

Jordan Wirfs-Brock / Inside Energy

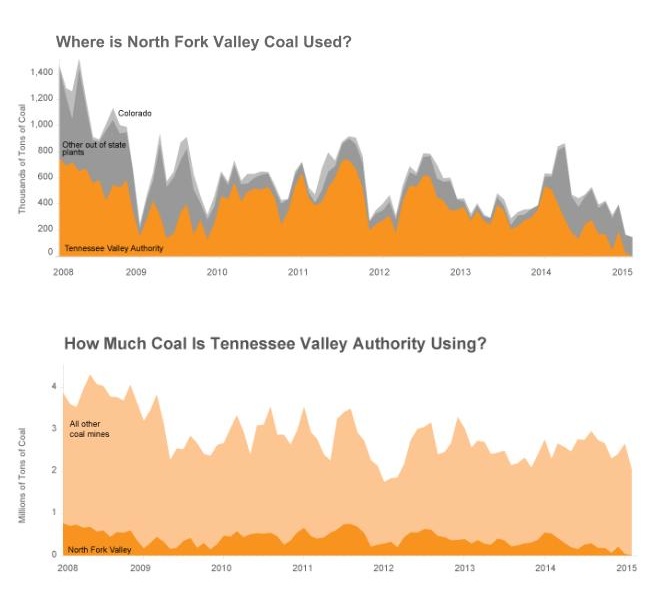

Coal production in the North Fork Valley is has declined 90% since early 2008. And while the Tennessee Valley Authority used to regularly buy three-quarters North Fork Valley coal, in recent months it has purchased less than 15%. Data Source: Energy Information Administration, Form EIA-923.

There are two major reasons for the decline. First, regulations. When the Clean Air Act was amended in 1990, the utilities in the Eastern United States, like the Tennessee Valley Authority, began switching to Western coal because of its much lower sulfur content. For a long time, TVA bought 70 or even 80 percent of the coal mined in the North Fork Valley. Now that’s down to 15 percent.

In addition, TVA is closing a lot of its older coal plants, so the utility is buying less coal, period. But it’s also buying less Colorado coal because the coal plants that are still open all have pollution controls, or scrubbers, that allow them to burn higher-sulfur local coal produced in the nearby Illinois Basin.

“We’ll be able to play a little with the blends that we use,” said TVA spokesman Scott Brooks. Decisions about where to buy coal “change a little when we are able to burn a higher sulfur content.”

The North Fork Valley is located in Delta County, Colorado and Brad Harding is director of Delta County Economic Development. He said the decline of coal production is, “definitely an example of how macroeconomic events and decisions at the highest level can filter down to a small community.”

Cheap natural gas — much of it coming from fracking— is also contributing to the switch away from coal. Natural gas emits about half as much carbon dioxide as coal when burned, something that is increasingly important under the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed Clean Power Plan, which is designed to reduce the carbon emissions from the electricity generation sector. Indeed, the EIA predicts that coal generation will fall even further under that plan.

There have been proposals to open parts of the North Fork Valley to drilling and fracking (the Bureau of Land Management held one of the fieriest public meetings I’ve ever attended on this issue in January 2013), and that is something coal miners feel decidedly mixed about. On the one hand, natural gas is just what’s undermining the coal industry. On the other hand, those jobs pay really well.

“We cannot ignore industries that are going to be job providers to this area,” Former coal miner Cliff Brewer said. “There’s nothing here. Trust me I’ve looked.”

There is one energy industry here that’s doing very well in the Valley: solar. Just down the road from the coal mines, Solar Energy International runs a training center to teach people to become solar installers.

“We’re growing so quickly I’m running out space for people,” said Executive Director Kathy Swartz as we walked around looking for a quiet place to talk.

The number of Coloradans with solar panels on their roofs has increased more than 50-fold since 2007. Interest in SEI’s classes is exploding. But that doesn’t necessarily translate into more high paying local jobs.

“Definitely no,” Swartz said, shaking her head and laughing. “The coal industry is unique like that. In the solar industry if someone were to work locally, probably that $25,000 to $30,000 annually would be a decent job.”

People are still moving to the North Fork Valley, but it’s often not for high-paying jobs. They’re here for the mountains, the quiet, the local food. Increasingly, people like Rene Atchley — the one whose family has been in coal for decades — don’t see themselves reflected in the newcomers.

“And that’s ok,” she said. “If that’s what they want, that’s great. If they’ve figured out how to live on that $7 to 10 dollars an hour and shoot up a prayer when they have to go to the hospital, I’m more for them than not.”

The organic farms and wineries are great, Atchley said. But for her, the most sustainable thing about this valley is coal.

What’s Next:

- Read more about the Future of Coal in our series, with Allegheny Front and West Virginia Public Media.

- Learn about the “War on Coal” in Politico’s great series of stories on power in this country.

- Follow the EPA’s efforts to clean up electricity generation with their proposed Clean Power Plan.