OSHA/CDC / OSHA/CDC

A worker observed by researchers from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health during exposure to silica dust on the job in this undated handout photo.

The disease dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, but it continues to kill workers today. Oil and gas is the latest industry to face its threat.

Silicosis is an incurable but entirely preventable disease caused by breathing in particles of sand, or respirable crystalline silica. Some particles are invisible to the eye but the perfect size to slice into the lung’s tightest corners. Breathing in too much silica can also cause lung cancer.

Sand is a key ingredient in hydraulic fracturing, but breathing in too much of it can be deadly.

Bill Cunningham / U.S. Geological Survey

Fine-grained silica sand is mixed with chemicals and water before being pumped into rock formations to prevent the newly created artificial fractures from closing after hydraulic fracturing is completed.

A 2012 alert and study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health raised an alarm that workers at fracking sites in Colorado and four other states were exposed to silica dust at levels that exceeded occupational exposure limits.

That exposure has not translated into patient diagnoses yet, according to interviews with four experts, but the disease can hide for a decade before causing symptoms. No one knows how many oil and gas workers may have already been exposed.

Still, many companies in the industry have responded by changing the way they handle frack sand. New innovation and investment suggests that a technological fix can protect workers while boosting efficiency. The changes are as much a way to improve operations as to strengthen worker protections.

Dangerous sand dust

At its worst, dust clouds full of silica can bloom in the air at an oil and gas well.

Sand first arrives at a site in a truck, then travels through a few pieces of machinery – called the sand mover, transfer belt and blender hopper – before it plunges underground in hydraulic fracturing fluid. The fluid fissures rock underground and the sand props open the fissures so oil and gas can flow out.

The problem is this: the more the sand moves around above ground, the finer it grinds and the more dust it releases into the air. Often, trucks offload sand using compressed air, blowing it aloft.

New businesses have formed to deliver sand without the dust. Instead of moving sand on its own, they keep it in a box resembling a metal freight container. When a crew is ready for the sand, they release it from the bottom of the box using gravity, not air pumps.

U.S. Well Services uses a system supplied by Houston-based SandBox Logistics on two of its nine frack fleets. The company already used a dust filtration system and wanted to save money on trucking, CEO Brian Stewart said.

“We happened upon them because we were looking for a logistics solution,” he said.

Liberty Oilfield Services’ two Colorado-based frack crews also use SandBox, and the company has plans to extend the system to its four remaining crews, spokesperson Audrey Carlson said. A gravity-fed system is quieter than the traditional way of delivering sand with pneumatic pumps, so it cuts down on noise and community complaints, she said.

“I think this will become an industry standard,” Carlson said.

Montana-based Grit Energy Solutions and Georgia-based Portare are two other companies offering a similar gravity-fed system.

Alberta-based Calfrac Well Services implemented its own fix, called “Sandstorm,” to deliver and process sand at a frack site. The system contains sand through covered conveyor belts, enclosed storage containers and a remote controlled robot.

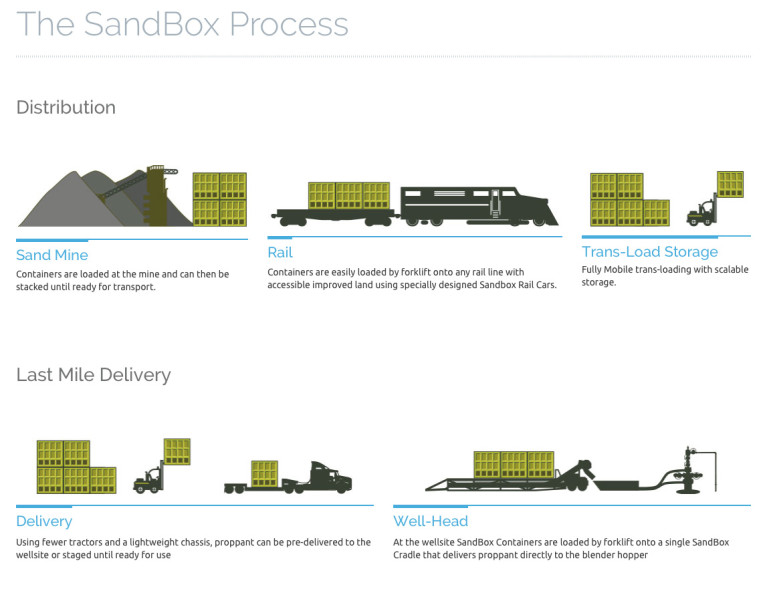

SandBox Logistics

An illustration by Houston-based SandBox Logistics of the process they use to provide containers of sand that are used in the hydraulic fracturing process.

Compared to traditional pneumatic systems which take 40 minutes to unload, the new system takes 9 to 12 minutes, president for U.S. operations Fred Toney said, and needs five fewer people.

“It actually costs us less to operate in the end,” Toney said.

The nose on a dime standard

The U.S. government has warned about the dangers of breathing silica dust as far back as 1938. In 1971, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) set the current standard for workplace exposure.

A 1971 OSHA regulation sets the amount of silica that can be inhaled in a day to about the amount that can fit on FDR’s nose on a dime.

It says in the span of a workday, you can breathe in about twice as much dust as can fit on President Franklin Roosevelt’s nose on the face of a dime. If you’re in construction, the standards is for five times FDR’s nose in silica.

It might seem small but it’s too much dust, according to doctors and OSHA itself. Breathing in silica can also lead to lung cancer, kidney disease, and an increased risk of tuberculosis.

“I think for the current OSHA standard, the allowable limit for respirable silica is high and does not protect many workers adequately,” said Dr. Cecile Rose, lung expert at National Jewish Health.

Since 1974, OSHA has unsuccessfully tried to update the standard.

The latest attempt was in 2013 when OSHA proposed new rules to halve the amount of silica that workers can breathe in. OSHA claims tightening restrictions will save 700 lives and prevent 1,600 people from contracting silicosis annually.

Many industry representatives oppose greater government restrictions on worker silica exposure.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce commented to OSHA that “there is no need for, or benefit from, this OSHA rulemaking.”

“This proposed rule is not technologically feasible for the hydraulic fracturing industry,” according to The American Petroleum Institute’s comments to OSHA.

Not everyone in the oil and gas industry agrees.

CEO of Sandbox Logistics, Josh Oren, testified in April 2014 OSHA hearings in support of new rules, saying the technology exists (including in Sandbox products) to implement the stricter standards.

In interviews, company executives also say the new rules are feasible.

“We already exceed those requirements, so it is possible,” U.S. Well Services’ Stewart said.

“With this Sandstorm system we’re well below even the future OSHA (silica) standards,” Calfrac’s Toney said, operating at “about half of what the future standards will be.”

‘Dust is my enemy’

It’s already too late for workers in other industries diagnosed with silicosis.

Joe Mahoney / Rocky Mountain PBS

A dust mask lays in front of Gilbert Banuelos as the former factory worker rests after a few minutes of gardening at his Erie, Colo., home. Banuelos’ lungs are riddled with scarring from silicosis he says he contracted working at a diatomaceous earth factory in California for 17 years.

Gilbert Banuelos, for example, who gasps for air during the smallest chores. A few minutes of plucking weeds from the garden or sweeping the back patio knocks him into a chair. If he’s not careful, it can knock him unconscious.

His wife of nearly 35 years, Valerie Banuelos, rolls over the green oxygen tank. Gilbert Banuelos inserts the tube into his nose and heaves in air.

“I have to be his mom sometimes because he won’t stop,” said Valerie Banuelos and wiped tears off her cheeks. Most of her husband’s former co-workers are dead, she said.

After high school, Gilbert Banuelos worked for 17 years at a diatomaceous earth factory, manufacturing gritty mineral material that’s used in everything from pool filters to makeup. Inside, dust piled up on the floor and glinted in the California sunshine that streamed through the skylights, Banuelos said.

Now in his 60’s and living in Erie, Gilbert Banuelos’ lungs are riddled with scars from silicosis. The Banuelos are waiting to hear if he is a candidate for a lung transplant.

“Dust is my enemy,” Gilbert Banuelos said.

Every year it gets harder and harder to breathe.

__

This report is part of a collaboration with the Center for Public Integrity on their Unequal Risk series examining toxic substances in the workplace. Read more at http://www.publicintegrity.org/

__

Inside Energy brings you this report in partnership with Rocky Mountain PBS I-News. Learn more at rmpbs.org/news. Contact Anna Boiko-Weyrauch at abw@rmpbs.org.