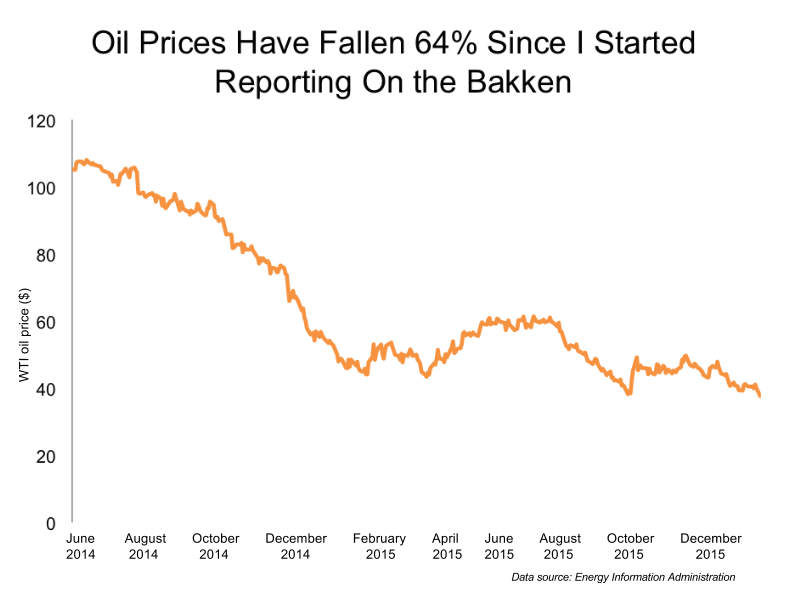

Call it a bust. A correction. A slowdown. A time to catch our breath. Whatever your euphemism, the numbers don’t lie: the price of oil is down, way down, and that’s had a huge impact on North Dakota, the country’s number two oil-producing state.

It’s also had a big impact on me. I moved to North Dakota in June 2014 — pretty much the beginning of the end of the boom, although I didn’t know it at the time. Back then, North Dakota was the last bastion of the American Dream, a place where anyone with a high school education and a willingness to work could get a good-paying job. It felt like everyone was hiring, everyone was optimistic, everyone was hustling.

Emily Guerin

Bismarck, North Dakota. November, 2014.

Almost immediately after I arrived, things started to change. There were signs that summer that American oil companies had gotten too good at producing oil from places like the Bakken, creating a glut. Prices started sliding on their own, but then in November, OPEC decided not to cut back on production, meaning the world market would continue to be saturated with oil. Prices fell faster after that. As one oilman told me right around the OPEC decision, “we’re not slitting our wrists, but it’s terrible.”

Over the past year, I’ve been asking everyone from truck drivers to RV park owners to school superintendents about how the falling price of oil has affected them. And along the way, I’ve gotten a lot of unexpected financial advice. So I’m passing those tips along to you, dear readers. Here are five things I’ve learned about managing my money from reporting on the oil bust.

1. Don’t adopt an expensive lifestyle that traps you in a job you hate.

Last week I met a truck driver who had been hauling crude oil for four years. That’s three years longer than he intended. Why did he stick around? Because he and his wife got giddy with his six-figure salary and bought a new truck, a boat and other shiny things. Suddenly, he needed that income to make the payments on all those new toys. It’s called “the golden handcuffs,” and it happens to a lot of oilfield workers, as my colleague Leigh Paterson has reported. If you don’t like your job all that much but it pays you well, don’t get accustomed to an expensive lifestyle. It will make it harder to quit.

2. Don’t go into debt if your income varies wildly or your industry is unstable.

Let’s stick with our trucker for a minute. When oil prices started falling, the first thing this guy’s company did was cut everyone’s hours. That meant no one was getting overtime anymore, which is how most oil workers make most of their money. Suddenly his income was cut nearly in half. Making those truck payments seems extra unlikely now.

So many people here have told me to avoid large debt loads, from real estate developers to people working for oil companies to small town mayors. It’s practically a refrain in the oilfield, “Want to know who’s screwed right now? Just look at who is in debt.” So if you are working in an industry whose employment needs and overall health fluctuate wildly, whether it’s based on a commodity price or because you’re a freelancer or whatever, don’t go into a lot of debt.

3. If you are in a job that’s not ideal, don’t lose track of why you are doing it. Know when it is time to leave.

I hear things like this from oilfield workers all the time. “I’m only staying here for 2 years … I’m working this job until I pay off my medical debt … I’ve re-done three rooms of the house and I have one more. When that’s done, I’m going back home.”

I think this is super smart, especially when you’re doing a difficult job you may not like that much but that pays really well. If you’re in it for the money alone, know exactly how much you need to hit your goal and then get out of there. Don’t just work for the sake of working, be deliberate and know why you are sacrificing your quality of life and how much longer you intend to do that.

4. Diversify.

Last March, I interviewed the owner of a small oilfield services company. With oil prices down, his core business area — hauling things around the oilfield on demand, a subspecialty called “hot shot driving” — had started to slow, too. So he diversified. He got a bunch of power washers and put his drivers to work washing drilling rigs, which needed to be cleaned and stored since so many of them weren’t being used to drill for oil anymore with the slowdown. Many of his drivers were also trained as welders, so when hot shot driving was slow he’d shift them to doing repair work. Smart.

Emily Guerin

Sleeping in my car in October 2014 because all the hotel rooms were full while on a reporting trip in New Town, North Dakota. This doesn’t happen anymore.

5. If everything is collapsing around you, don’t be afraid to completely change what you are doing.

A lot of people in the Bakken did not start out as oilfield workers. I’ve met a Hewlett-Packard employee who lost his retirement savings in the recession and wound up hauling wastewater as a truck driver. I’ve met a logger from Oregon who fled the state after saw mills closed and ended up owning an RV park here. I’ve met a journalist who now works on a drilling rig. These people have taught me not to completely derive my identity and self-worth from my profession, and not to be afraid to reinvent myself if the situation calls for it. Which given the uncertain state of journalism in the 21st century, is probably a good lesson.