Everyone’s heard the story of the oil boom and its ugly twin, the bust. A sleepy community transformed overnight by a wave of rapid growth. Workers flock to the area, sleeping in RVs, hotels, and cheaply-built apartments. Eventually, there’s a bust, and locals are left with scores of empty buildings and wondering what happened. But does it have to end this way? I went to Watford City, North Dakota, to find out.

The first thing you have to know about Watford City is that it’s not a city. It’s a small, farming town on the northern Great Plains, surrounded by wheat farms and cattle ranches. Since the latest oil boom began here around 2009, Watford City has grown astronomically.

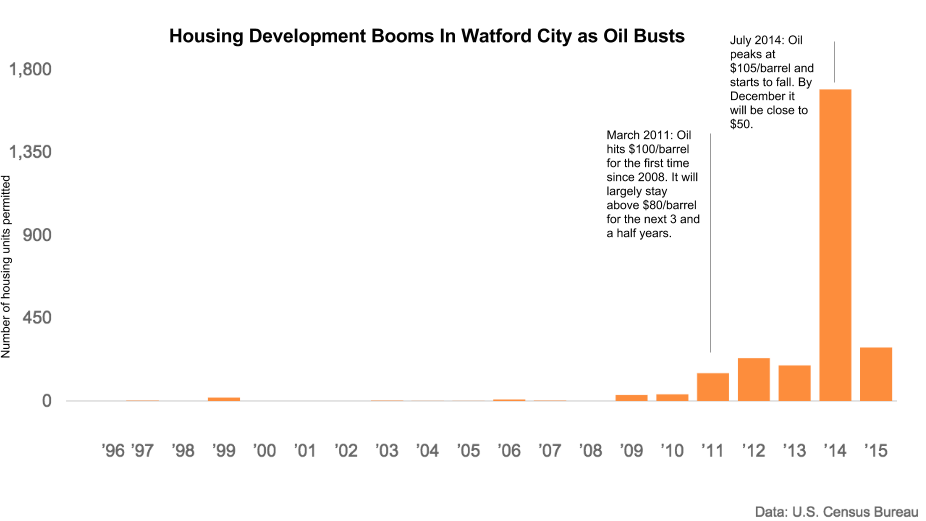

The latest Census estimate from July 2014 puts the population at 4,200, up from 1,300 ten years earlier, but local officials say that’s woefully inaccurate. They guess there are around 12,000 people in town based on the number of people flushing toilets and using electricity. Watford City issued close to 1,700 building permits last year, up from one — yes, one — ten years ago.

That’s worrying to people like Bill Caraher, a professor at University of North Dakota who studies housing in the Bakken oilfield.

“Man, I mean driving out the eastern side of Watford City and seeing those hills covered with houses. Oh my gosh, I hope they’re not making a mistake,” he said. “‘Cause we love the people in Watford City. We really want them to be able to manage this and be successful.”

Here’s what boom towns like Watford City: overbuilding when times are good, and then getting stuck with tons of debt and abandoned homes when the economy busts. It’s happened so often in North Dakota history, there’s even a term for it — the “too much mistake.”

But in this most recent boom, the biggest in state history, Watford City is determined to avoid the “too much mistake.” To find out how, I went to talk to Watford City Mayor Brent Sanford.

Sanford said in the last oil boom of the early 1980s, Watford City paid to build a lot of new infrastructure for housing developers, from roads and grading to curbs and gutters to sidewalks. All the developer had to do was put up the houses.

But when the price of oil crashed, developers abandoned their housing complexes and people moved away. The city was left with the empty lots, and there weren’t enough people left in town paying property tax to cover all those new roads and sidewalks. Other oilfield towns went bankrupt. Watford City managed to avoid it, barely.

“We don’t want to get into that situation,” Sanford said.

That’s why this time, the city made developers pay to build their own roads and extend their own sewer lines; in turn, developers charged tenants Manhattan-level rents. In March 2014, for example, rents averaged $2800, according to Trulia.com‘s rent monitor.

But not everyone lives in permanent housing. Watford City is ringed by man-camps, clusters of mobile homes or RVs where many oil workers stay. Local officials are also worried about what happens to those developments if the economy tanks.

Jim Talbert, planning director of McKenzie County, where Watford City is located, took me on a drive to show me what the county is doing to avoid getting stuck with abandoned temporary housing. We drove by a barracks-style man camp, where little white trailers laid out in neat rows on a flat gravel surface. I didn’t see a single person.

Talbert sighed, “What we are looking at is a fairly low occupancy rate.”

At $40 oil, a lot of these places are less than half full. Some of them have already gone out of business. But since 2013, when the county enacted zoning ordinances for the first time, every new man camp developer has had to buy reclamation bonds, just like oil companies have to do when they drill wells. The bond is 150 percent of what the city estimates it would cost to bring the fields back to farming. That means they county won’t get stuck cleaning up the mess.

“When it’s done, we don’t want to just have all these spots we have nothing to do with,” Talbert said. “We want it back so it can be productive and beautiful.”

It’s still shocking to Brent Sanford when people ask him, is Watford City growing too fast? That’s because not too long ago, the town had the opposite problem. When he graduated high school in 1990, “basically there were no jobs. We all would leave and go to college and move away, and come back for Thanksgiving and Christmas.”

Sanford thinks they still need more housing, especially single family housing. That’s what Sanford believes will provide some stability to the town — and convince some of the transient oil workers that this little town is a good place to put down roots. He hopes that’s enough to avoid the too much mistake.