Natural gas has lower emissions than other fossil fuels, and so it is often touted as a “bridge fuel” to ease our country’s transition from big polluters like coal and oil to a cleaner, greener, low-carbon energy future. But methane leaks as a result of natural gas production may put that clean gas bridge in doubt.

This question came to us at a TedX event in Denver last year. With federal regulations to limit methane emissions currently under review by the Trump administration, it is a timely issue for review.

What Is Methane Anyway?

Methane is the primary component of natural gas, which, when burned, releases less harmful air pollution than other fossil fuels. For instance, burning natural gas releases a third as much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as burning coal. Natural gas also releases less air pollution hazardous to human health, such as particulates and the chemical ingredients that can form ground level ozone. More and more coal-fired power plants are switching over to natural gas because it is less expensive and provides an easier way to meet air quality standards. As a result, greenhouse gas emissions are reduced.

However, when methane leaks, it is also a powerful greenhouse gas. It traps at least 25 times more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide over the long term, so methane leaks might be undoing much of the attempted reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

It’s also flammable. A methane leak can lead to dangerous fires. It’s implicated in the April 2017 home explosion in Firestone, Colorado. Methane leaks can also lead to the formation of ground level ozone, a hazardous air pollutant that causes asthma attacks and lung damage.

Where Does All This Methane Come From?

Methane forms underground with other fossil fuels. In areas with oil and gas development, methane can escape from wells, storage tanks, pipelines, and other infrastructure. Most of this so-called “fugitive methane” is leaking directly into the air at active well pads. In some places, methane escapes naturally into the air – for example, at the methane seep in the Four Corners area.

Dr. Joe Ryan, AirWaterGas, University of Colorado

Flare at a Colorado well pad.

The flares often seen at oil and gas wells are methane that is being burned off. This releases pressure, avoiding explosion risks, and avoiding releasing methane directly into the atmosphere. But flaring methane emits carbon dioxide, another greenhouse gas albeit with less heat-trapping ability than methane. In locations like Colorado with significant natural gas infrastructure such as pipelines, small amounts of methane are burned in flares. But in the Bakken oil and gas field in North Dakota where gas is not used, there is so much flaring gas that the area shows up as a bright spot on images of the earth from space. It appears as bright as cities even though the area is sparsely populated.

NASA Earth Observatory/NOAA NGDC

Natural gas flaring in the Bakken Field in North Dakota and the Eagle Ford Field in Texas, is visible from space.

Finding The Fugitives

Fugitive methane leaking from oil and gas development is a colorless and usually odorless gas. Methane on the lam is not easy to find, but researchers and regulators have ways of tracking it down.

On the ground, researchers can locate methane using mobile labs – vehicles outfitted with sophisticated equipment for detecting chemicals in the air. To find methane and other emissions from oil and gas operations, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientist Dr. Gabrielle Petron drives her mobile lab, a large van she filled with sensors, around the roads of Weld County, Colorado. A boom that projects from the front of the van collects air samples that are routed through instruments. Using this method, Petron found that emissions from oil and gas were about twice as high as the emissions estimates that policy makers rely upon, which are reported to the Environmental Protection Agency by the oil and gas industry.

Patrick Murphy, Boulder County Public Health / Boulder County Public Health

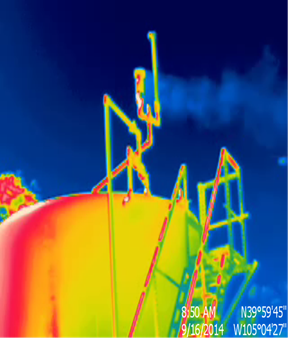

This photo, taken with an infrared FLIR camera, shows fugitive emissions escaping from a Colorado storage tank.

In the air, measurements from sensors on research planes can let us know how much methane makes it into the atmosphere. This allows researchers to get a sense of the total amount of methane released into an area, not individual sources. In 2012, Petron and her team sampled air from a plane over the oil and gas field in and around Weld County. Based on their samples, they calculated that 19 metric tons of methane were emitted per hour from oil and gas wells and pipelines in the Weld County area. That’s three times more methane than EPA emissions estimates from the same timeframe, meaning there was far more methane leaking from this area than reported by the oil and gas industry.

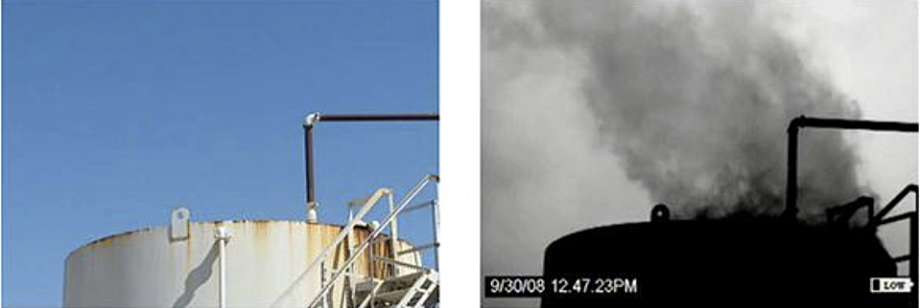

On well pads in Colorado, infrared cameras that make methane visible are used to identify leaks. The use of these cameras has grown since Colorado methane regulations were put in place in 2014. Under the Obama administration, federal rules to limit methane leaks were developed based in part on Colorado’s methane regulations. Under President Trump, the EPA is working to either suspend or reverse those rules. But, in a ruling earlier this month, a federal court said these rules can not be suspended. The federal regulations to limit methane leaks are still under debate in Washington.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency / EP

Methane escaping from a storage tank can’t be seen in regular light (left) but can be detected with an infrared camera (right).

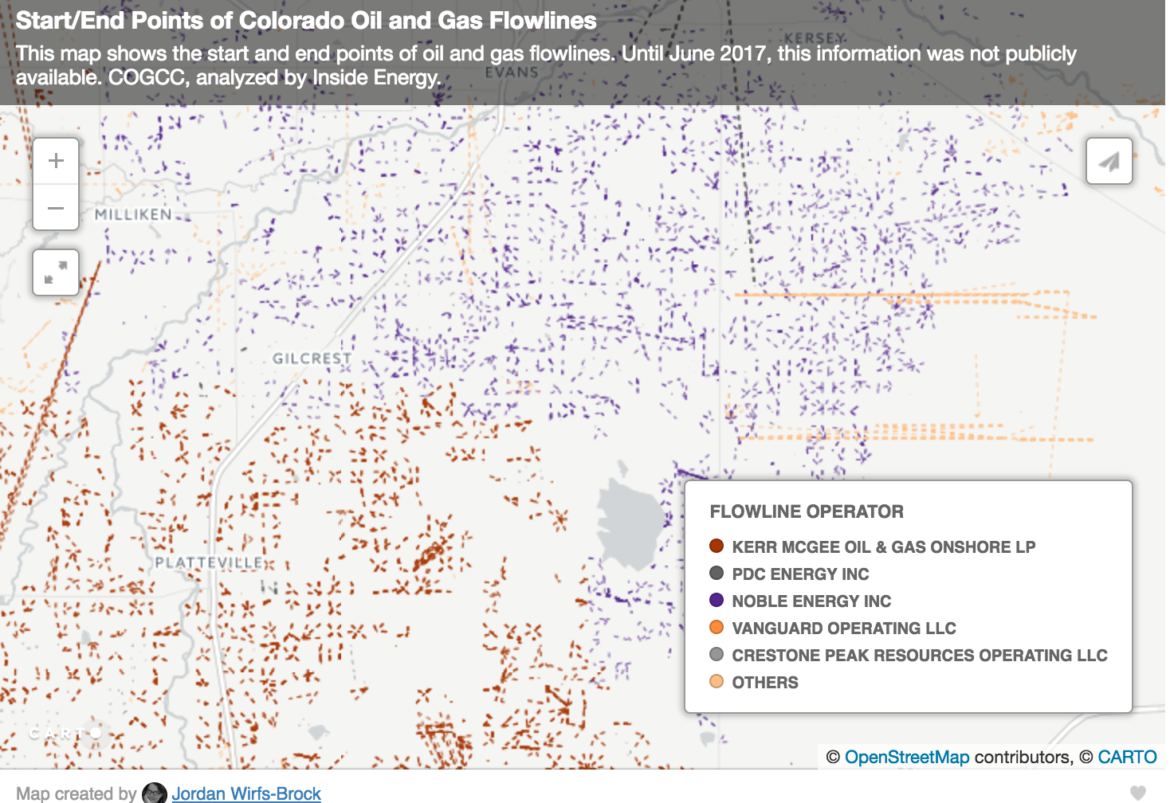

But not all leaks occur at well pads. The fatal explosion in Firestone, Colorado earlier this year is evidence that methane and other hydrocarbons can leak from older oil and gas pipes. To find out where else fugitive methane may be lurking, Colorado issued an order in May 2017 requiring oil and gas operators to share the locations of all pipes used for oil or gas that are within 1000 feet of a building. Using this information, Inside Energy created a map of oil and gas infrastructure in Colorado. The new order also required operators to census all pipes, no matter the distance to a building, and verify pipes that are no longer in use are sealed properly and marked with fluorescent paint.

Identifying The Source

Fugitive methane from oil and gas development is not the only way that humans are releasing methane into the atmosphere. Methane is also is released at farms due to cow digestive processes (think farts), at landfills due to decomposition, during biomass burning and wildfires, and in rice paddies. Additionally, methane is released into the air as the climate warms and frozen soils thaw in the Arctic. Methane is also trapped within ice on the ocean floor. There is concern that as the Earth warms these frozen deposits will thaw and methane will bubble to the atmosphere.

To pinpoint the source of methane in the air, researchers must look at chemical differences in air samples and geographic location to figure out which methane is from which source.

While it’s still not easy to catch this fugitive, it is vitally important to capture and contain these kinds of emissions. Thankfully, new science, engineering, and technology advances are increasing the number of methods that we have for finding leaks, tracking fugitive methane, and keeping it from escaping.

This story was made possible by collaboration between Inside Energy and AirWaterGas, a Sustainability Research Network funded by the National Science Foundation.