Elaine Crumpley / Citizens United for Responsible Energy Development

Ozone in Pinedale, Wyoming

The mountainside community of Pinedale, in southwestern Wyoming, used to be known for its clean, fresh air. Dave Hohl, 74, has lived in Pinedale for 15 years with his wife. He remembers going cross-country skiing about ten years ago and seeing a brown tinge to the air.

“As I remember, I was in bed for a week or so with something like the flu, it felt like, but it didn’t seem like the flu,” Hohl said.

Around 2005, the Upper Green River Basin began monitoring for ozone and levels were incredibly high. The dirty air caused coughing, nose bleeds and chest pain among the locals.

Dave Hohl recalls, “Everything from doctors in Jackson not allowing newborns to come back to Pinedale because of the air quality, to kids not being able to go outside for recess.”

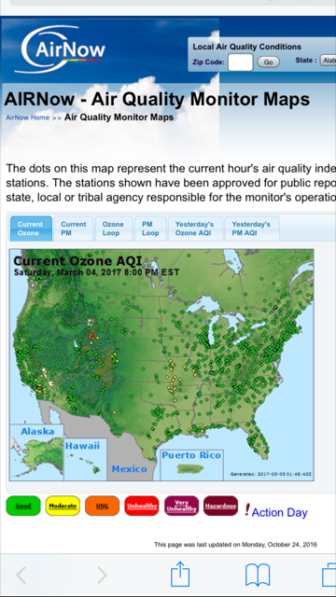

The basin’s conditions are perfect for ozone formation due to reflective snow, sunlight, and nearby energy development. Before 2012, according to a report from Utah State University, the Upper Green exceeded federal ozone limits 37 times. So bad, the region was found to be outside of compliance with federal air quality ozone standards.

Wyoming’s Department of Environmental Quality, DEQ, had no choice but to come up with a plan to reduce ozone. In 2013, guidelines were put in place requiring stricter controls on new or modified wells if emissions were above four tons per year — specifically, emissions that lead to ozone like nitrogen oxide and volatile organic compounds, VOCs. The controls must reduce certain pollutants by 98%. In 2015, those guidelines were extended to cover older wells too.

Elaine Crumpley / Citizens United for Responsible Energy Development

Fracking operations in Pinedale, WY

Now, this Wyoming region has some of the strongest emissions regulations on the oil and gas industry in the country. Similar federal emissions rules were released by the Environmental Protection Agency in May of last year and cited the Upper Green’s experience working to reduce emissions that lead to ozone as a positive example. This week, a federal court mandated the EPA begin enforcement of those rules nationwide.

Back in 2013, companies had to find ways to comply with the new regulations. One of those companies was Ultra Petroleum.

Elaine Crumpley / Citizens United for Responsible Energy Development

Ozone levels throughout the US, showing high levels in the Upper Green River Basin

Erika Tokarz is a regulator for Ultra, one of the major energy companies in southwestern Wyoming. She walks along their Riverside pad in the Pinedale-Anticline field and points to one method they use to keep ozone down — a row of large, light blue tanks that inject chemicals to remove nitrogen oxide. It’s called an SCR system or selective catalytic reduction system.

Companies elsewhere are also using everything from acoustic detectors that use sound to identify leaks to GPS measuring of gas concentration.

By 2016, ozone levels had fallen enough that the region was back in compliance with federal ozone standards, according to Keith Guille with the DEQ.

Wyoming task force meeting in 2012Nancy Vehr, DEQ air quality division administrator, says changes were successful because multiple stakeholders were involved.

“It’s not something the department can do on its own. The citizens can’t do its own, industry can’t do it on its own, it takes all of us and everybody plays a part,” she said.

Yet many in Pinedale continue to believe the current rules do not go far enough. Linda Baker, with the Upper Green River Alliance, is one of them. This past winter ozone levels spiked again in the Upper Green River Basin.. And now there’s a proposal for a new natural gas project that may install 3,500 new wells in the area. Baker says she believes there should be tighter guidelines to keep ozone levels down.

“A slower pace of development, fewer numbers of wells per year, is really the only way that I can see for keeping our air clean,” Baker said. “But we have begun to establish better standards here. That could be the boilerplate for other parts of the country where ozone is also a problem.”

The new rules on the federal level would mandate similar guidelines for oil and gas development across the country. But they’ve been the subject of legal ping-pong in Washington — in place, and then on hold, and now in place again. Just this week a court ruled the EPA will need to begin enforcement.

Gas companies in the Upper Green Basin were not able to give hard numbers on how much their mitigation efforts cost. And cost is a key issue for many in the industry who oppose federal rules to reduce emissions.

For now companies nationwide will begin compliance with the regulations – regulations that look very much like what’s going on in Wyoming’s Upper Green River basin.

What’s Next

- Regulations targeting emissions has been in the news lately. See what our colleague Dan Boyce filed for Marketplace.

- Listen to how climate change could actually help the coal industry

- Take a look at how the solar panel market is taking a hit this yea