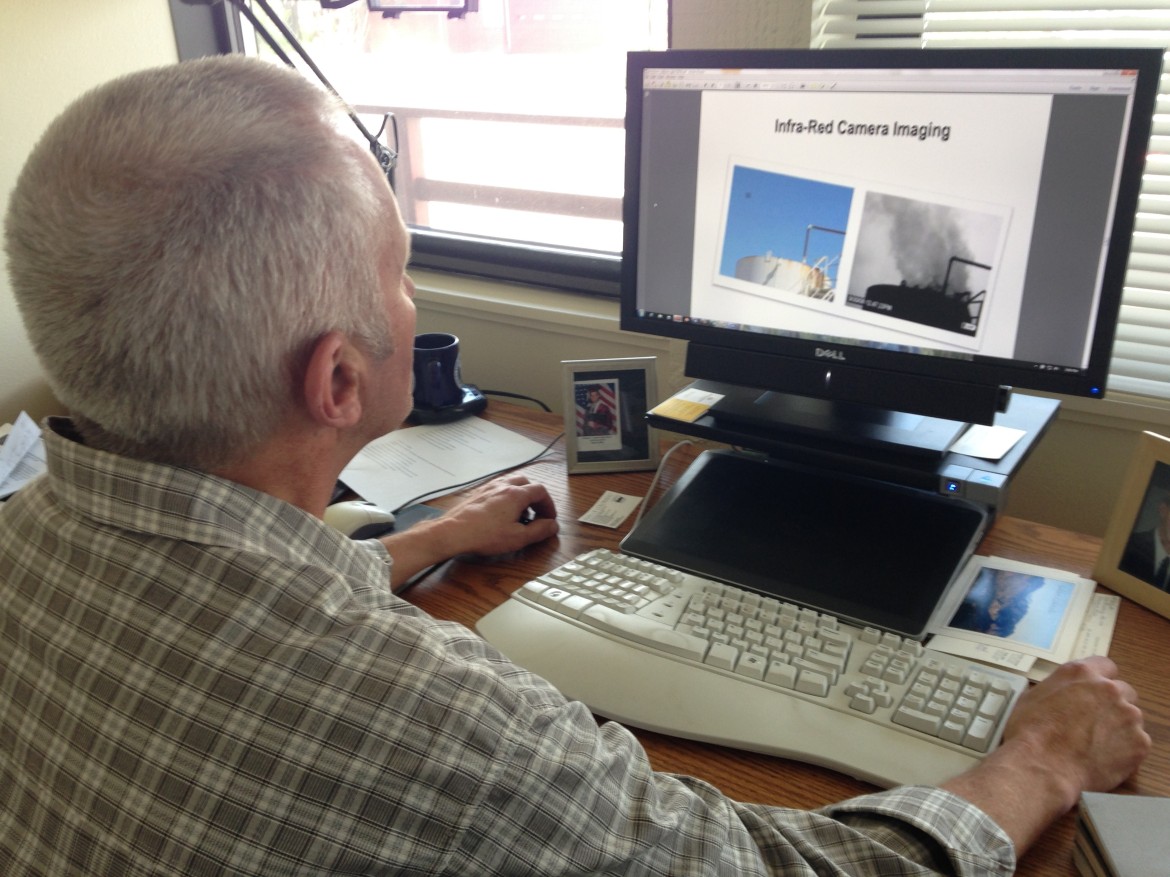

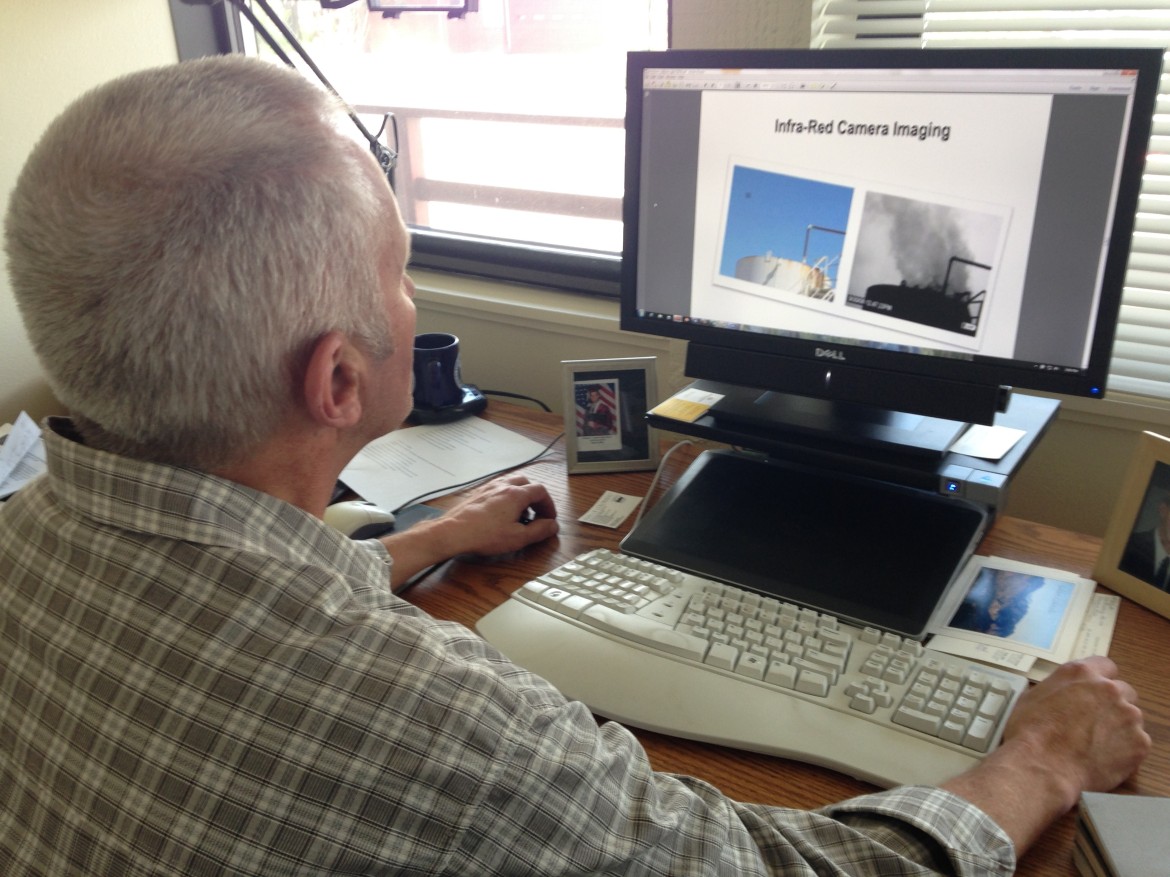

Dan Boyce / Inside Energy

Gary Graham with Boulder-based Western Resource Advocates compares how methane emissions at drilling sites can be seen with infrared technology.

New regulations begin to go into effect in May in Colorado to cap methane emissions from oil and gas drilling sites. These regulations could prove to be a model for the rest of the country. The measures are also groundbreaking because of the rare collaboration between industry, environmentalists and state leaders which led to the rules.

The crackdown focuses on so-called “fugitive emissions” from the storage tanks on oil and gas sites. These emissions consist of methane and a bunch of other baddies known as “volatile organic compounds” (VOCs) which can lead to the formation of ozone. A recently released report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has found that ozone levels in parts of Colorado were far higher than anticipated. See Inside Energy Now for more on that report.

“[It’s] as simple as tightening a valve or replacing a part, I mean these are not complicated fixes,” says Doug Hock, a spokesman for Encana, one of the oil and gas companies that helped craft the new methane regs.

Proponents say the rules are good for the environment and they say the companies stand to profit from selling the gases they capture, making back the money they spent fixing the leaks. Many are calling that a win-win, but economist Alan Krupnick is not so sure.

“If it’s so profitable to do that, to capture this methane, why aren’t the companies doing it now,” says economist Alan Krupnick, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan think tank Resources for the Future.

“They’re doing this to improve their image,” Krupnick says of the industry.

And the state of Colorado is on board.

Will Allison leads Colorado’s Air Pollution Division. He calls the implementation of the new regulations significant, in part, because of what he describes as the intense approach leading up to this point.

“[There were] five days of hearings, back-to-back-to-back in front of our air quality control commission,” says Allison of a process that consisted of meetings, drafts, and compromises that stretched on for more than a year.

Last November, though, they reached consensus. Oil and gas companies have to fix leaks and capture 95 percent of emissions. The rules gradually take effect over the next couple years.