In new findings published today, scientists studied drinking-water wells near shale gas drilling sites that had elevated levels of methane to figure out:

- Is the methane coming from drilling activity?

- And if so, where in the process is it coming from?

What did they find?

Methane gas is coming from natural gas extraction, and is escaping through leaks in the cement well casing and traveling into drinking water. The researchers concluded that, in eight clusters of wells in Pennsylvania and Texas, it wasn’t the hydraulic fracturing or horizontal drilling pathways that caused the leaks, but the cement well casings themselves.

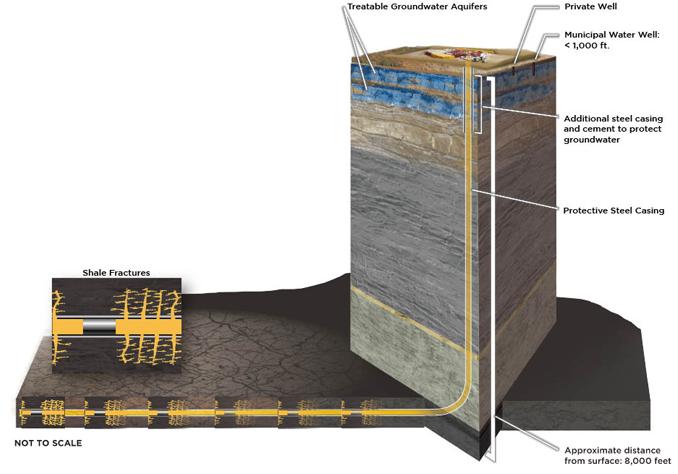

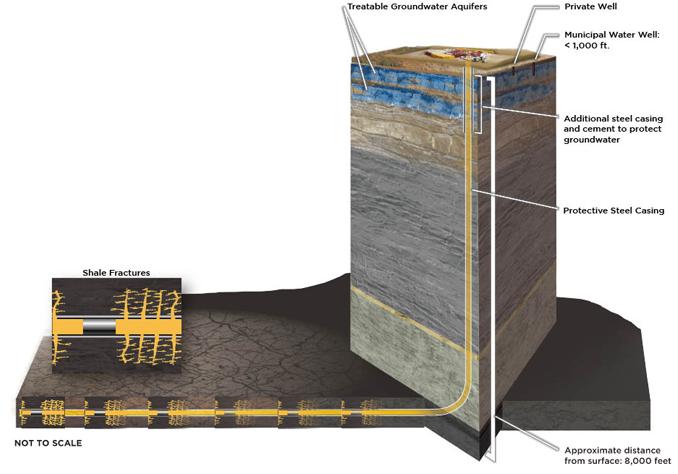

It’s easiest to understand this by looking at a diagram of a well:

Virginia Department of Mines Minerals and Energy

The study found methane was leaking through cracks and failures in the cement casing near the top and middle of the well, and not in the horizontally drilled portion.

The methane is coming from leaks and failures in the casing near the top of the diagram (near the depth of drinking-water wells) and not from the horizontally drilled, hydraulically fracked portion at the bottom. So leaked contaminants are mostly migrating horizontally, not vertically.

How did they do it?

The researchers didn’t actually track methane as it moved from a well, through the leaks in the cement casing, and into the ground water. They tracked noble gases – which are stable and don’t react with the environment or degrade over time – that move along with methane. Methane can get into drinking water all sorts of ways, and noble gases are a clever tool researchers use to distinguish between those pathways.

Why does everyone keep talking about methane if it’s not a health problem?

To be clear, methane itself doesn’t cause health problems (although in high concentrations it can be dangerous because it can explode). But where there’s methane, there are often other gases, like benzene, that can be harmful to your health. Methane and its more dangerous cohorts can move as gases or dissolved in liquid, which is why it’s important to know where leaks are happening.

What does this mean and why does it matter?

If we know a certain part of a natural gas well – the cement casings – is a pathway for contamination, then we can improve it and make it safer.

“People know how to put in good casing, but it’s definitely not done all the time,” said Mark Williams, a hydrologist at the University of Colorado who studies groundwater contamination but wasn’t involved in the study.

During boom times, development happens quickly, which often results in shoddy construction – like faulty casings, for example. And in some boom areas, research and regulations haven’t caught up to curb this problem.

“These regulations evolve over time,” said Williams.

And understanding how leaks happen helps us prevent contamination.

Find out more:

- Read the entire study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: “Noble gases identify the mechanisms of fugitive gas contamination in drinking-water wells overlying the Marcellus and Barnett shales”

- What do we know about oil and gas development and health? Read Inside Energy’s summary.