Travis Bubenik

Lucy and Clay Furlong, West Texas ranchers and the owners of this old mercantile store in Kent, TX., are gearing up to fight a proposed nuclear waste site in Culberson County.

Nuclear waste is not popular in any neighborhood. In West Texas, there’s a battle underway over a plan to create a above ground storage facility for high level waste. Its a bigger problem than West Texas – the nation’s nuclear power plants are quickly running out of room to store the waste.

This region has had a long and often contentious relationship with nuclear waste, stretching back to a years-long battle over a planned permanent waste site in the 1980’s and 90’s.

Opponents eventually won that fight, but a different site was later built in the Permian Basin.

Some now see West Texas as the ideal place to store higher-level waste from the nation’s nuclear power plants, since those plants are running out of room to do it themselves.

Ranchers don’t like the idea, and they’re already gearing up for a fight.

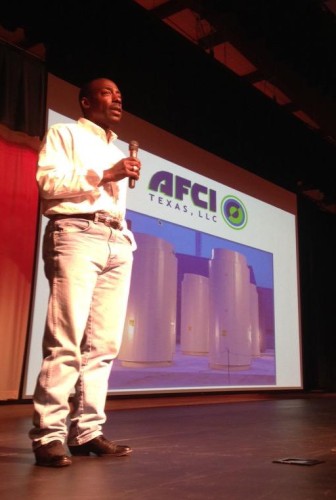

Travis Bubenik / KRTS

Bill Jones, Texas Parks and Wildlife Commissioner and co-owner of AFCI, Texas, speaking in Van Horn about his plan for a high-level nuclear waste storage site.

Bill Jones is a Texas Parks and Wildlife Commissioner. He’s also co-owner of the Austin-based waste company AFCI, Texas. In that role, he wants to bring used nuclear fuel from those power plants to an above-ground storage site in rural Culberson County.

But he’s been trying to do that for seven years. Even with supporters as powerful as former governor Rick Perry backing the idea of bringing nuclear waste to Texas, it has been a hard sell.

Four other West Texas counties have already told him, “no thanks.”

“It’s fair to say that we did not bring along the landowners with the process, as we have with this county,” Jones said at a recent community meeting in Van Horn.

There, he pitched the idea to locals and people from neighboring counties. He was grilled on the safety of it.

Later, he said it’s not like that Simpons-esque image people have of a nuclear site.

“Most have a Hollywood view of a green, goopy, highly-toxic material stored in 55-gallon drums with a skull and crossbones drawn on the drums,” he said, noting that won’t be the case with this project.

The waste would be stored in heavy-duty steel cylinders, the way it’s already stored at many of the plants that produce it.

“We are doing something that we are currently doing in this country very safely,” he said. “We’re just going to do it better, and in a remote location.”

The federal government has been looking for a community willing to take some of this waste from the power plants, while also seeking a permanent place to store it.

There are billions of dollars in a Nuclear Waste Fund to pave the way.

If the people here go with his plan, Jones said, some of that money – possibly millions – could wind up in Texas and here in Culberson County.

“If they satisfy themselves with the safety of it,” he said, “then I think it simply makes sense to explore the economic opportunities that come with it.”

His selling point to West Texans: If you don’t get in on this, New Mexico will.

Nearby counties there are looking at a similar plan, as is the low-level waste site that already exists in Texas.

That pitch hasn’t convinced people in the past, but this time could be different. Jones now has a powerful ally.

Remember that landowner Jones mentioned he’s got a better relationship with this time around?

That’s his fellow commissioner and Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission Chairman Dan Allen Hughes, Jr. His family owns the land where this site would be built.

That hasn’t convinced everyone.

“I just don’t really see how nuclear waste and Texas Parks and Wildlife go together, but I don’t know,” said Lucy Furlong, a cattle rancher in Culberson and Jeff Davis Counties. Her family’s owned the Long X Ranch since the late 1800’s.

Travis Bubenik / KRTS / Marfa Public Radio

Cattle ranchers Clay and Lucy Furlong say they were “horrified” to learn of a planned nuclear storage site that would be built just a few miles north of their Long X Ranch.

Old, grainy pictures of the ranch line the rustic walls of the main house.

She and her husband Clay say they didn’t know anything about nuclear waste until they found out just weeks ago that a site could be built a few miles up the road.

All they knew was how they felt about it – “horrified.”

Other nearby ranchers aren’t happy either.

“We’ve gotten together as landowners just talking,” Furlong says. “No one wants it.”

But at home, they’re thinking of what life might be like with that waste sitting nearby, possibly for a long time.

“They say it’s a storing facility, it seems like it’s gonna be for a very long time, 80 to 100 years, which we’ll all be dead then, who knows,” she said. “There’s caverns underground, water, we’re concerned about water, and the lights and the land value.”

Driving out to the proposed site, Clay Furlong points out an old railroad route Jones has talked about using to ship the waste in, but there aren’t any tracks on the ground. Just a dirt path, a sign that this plan’s still in its very early stages.

“There is a bit of a question mark here,” said Edwin Lyman, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists who focused on the future of nuclear power.

He says, the fact is, any project like this is going to be entering uncharted territory. It’s just never been done before.

“There’s always going to be uncertainty around the potential safety of the site,” he explained. “A lot of the analysis is based on paper studies and computer models, and there’s very little real-world testing of the integrity of spent fuel waste casks.”

This first-of-its kind project would have to be approved by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission before getting started – a process that could take years. And the beyond that – the government still has to figure out who exactly is going to oversee the future of nuclear waste storage management.

A bill currently in the Senate would create a Nuclear Waste Administration under the Executive Branch to tackle that job.