Everyone knows North Dakota is an oil state. But it’s the state’s coal industry that’s feeling the heat from the federal Clean Power Plan, which targets carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. Under the final version of the plan, North Dakota will have to cut its emissions by 45 percent – more any other state except Montana.

So it’s not surprising many North Dakotans feel they are being singled out for harsh treatment.

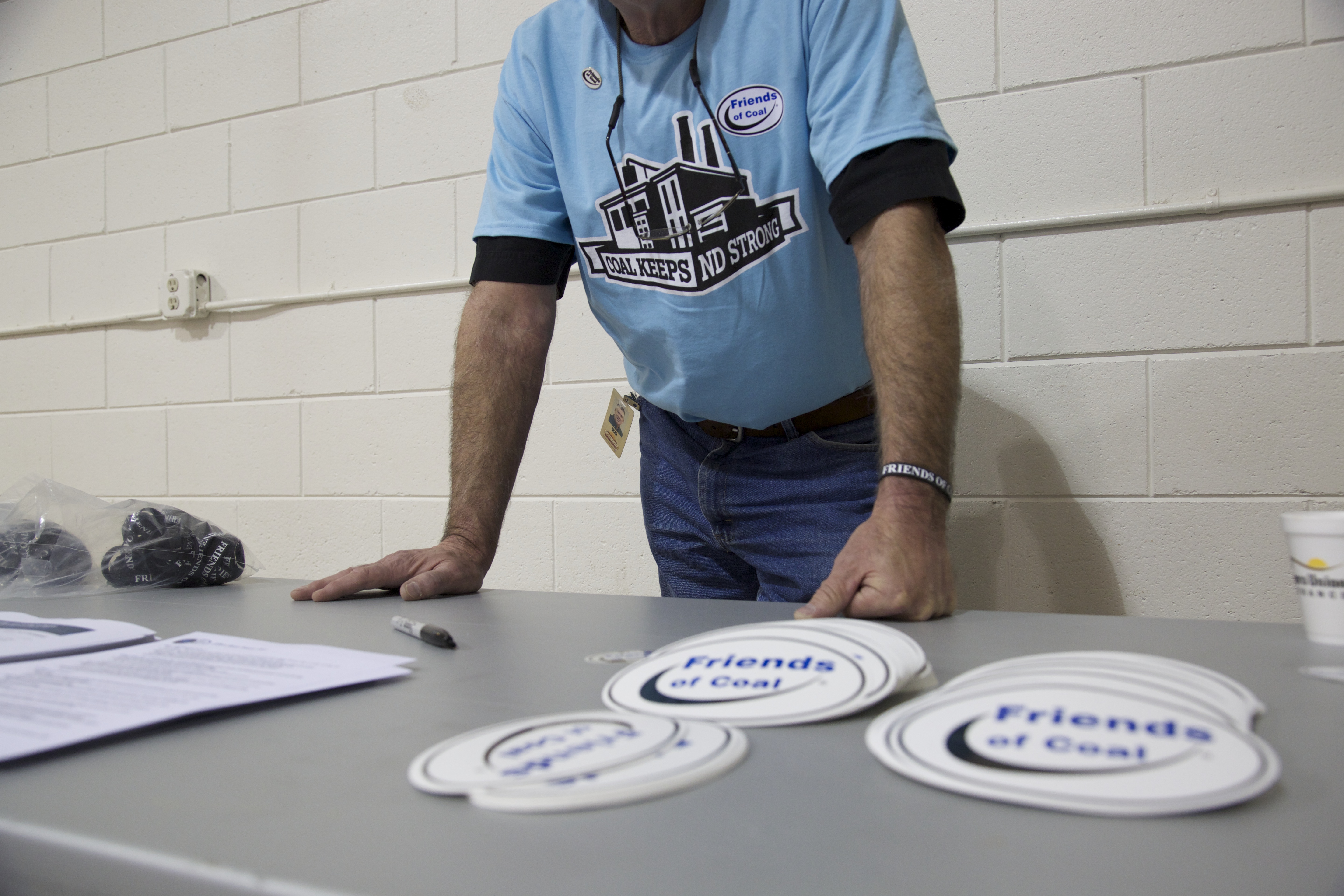

On a recent Thursday in November, about 700 of those North Dakotans packed into the gym at the Beulah Civic Center. They were there to show their opposition to the Clean Power Plan. Many had matching T-shirts and wristbands that said, “Coal Keeps North Dakota Strong.”

Others wore ball caps with logos of the coal mines and power plants for which they work. They shuffled through a long line to get a free dinner sponsored by local businesses, grabbing styrofoam cups of coffee and greeting friends.

It felt more like a pep rally for the local high school football team, the Beulah Miners, who would go on to win the state championship the very next day, than an informational meeting about a new federal environmental regulation.

Christie Obenauer was manning the coffee station that evening, but during the day she is the CEO of a local bank where about 75 percent of her customers have some tie to the coal industry.

North Dakota, population 740,000, isn’t a huge coal producing state – it ranks 9th nationally – but the industry has a big impact locally. Close to half the students at Beulah High School have at least one parent working at a one of the state’s four mines and six coal-fired power plants. The state exports 60 percent of its electricity to neighboring states, and most of what is consumed in-state is used by the industrial sector.

Obenauer was concerned that if “plants and mines can’t continue to operate as they do now, they (will) shut down or downsize, and people (will) lose their jobs.”

Luke Voigt had similar concerns. He’s the business manager for the local Boilermakers union, whose members maintain coal-fired power plants.

“If you don’t have a farm or ranch to go back to, I can’t imagine what anybody is going to do here,” he said.

But what about the Bakken oil field nearby? Couldn’t laid off coal miners just go work on a drilling rig?

Voigt shook his head. “The Bakken is a job. This is a career.”

The oilfield booms and busts, he explained, just look at what’s happening now: There are only 60 drilling rigs in the state, down from over 180 a year ago. In comparison, coal is stable.

“The oilfield, you go out and make a lot of good money for a while, and they work the snot out of you. But then when they’re done with you, they’re done with you. Where as here, constantly there’s work coming, there’s retirement and good benefits.”

Careers and coal communities – that’s what’s at stake. But it’s not clear yet how either will be impacted by the Clean Power Plan. Dave Glatt, head of the North Dakota Department of Environmental Health, is tasked with figuring out how to meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s 45 percent emissions reduction target for their state. At the meeting in Beulah, he was upfront with the crowd:

“At the end of the day I’m hopeful the power plants stay open and the coal mines stay open, but I can’t tell you that with 100 percent certainty because I don’t know what that plan is going to look like,” he said.

The graph above uses information provided by the EPA on individual state emission-reduction targets in the finalized version of the Clean Power Plan. States are ranked here by their amount of emissions in 2012. The gray bar shows the pounds per megawatt hour emitted by each state in that year; the orange bar shows the new 2030 target emission rates. The purple bar indicates the percentage reduction that target requires.

Glatt is considering turning in a state plan that doesn’t actually meet the 45 percent reduction, but keeps the state’s coal industry intact. It’s a risky strategy, because if the EPA doesn’t like it, they could impose their own plan. And if there’s one thing North Dakotans really hate, it’s being told what to do by the federal government, especially when it feels like what they’re being asked to do is unfair.

“They come out here, they have these public hearings, they pretend they’re listening, and they pretend they’re paying attention to what it is that we’re saying, and we try to reason with them,” said Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem, “and they ignore us.”

Stenehjem is suing the EPA, along with 26 other states, over what he sees as an overly harsh and illegal final rule. In the draft version, North Dakota only had to cut its emissions by 11 percent. In the final rule, the state’s target more than quadrupled.

“It was like sending your kid off to college and they come back at Christmas and you hardly recognize them anymore,” he said. “And that’s what happened with this rule. It was so totally different from what it was we had commented on.”

Even though he’s trying to change, delay or overturn the regulation, he doesn’t question the science behind it, and says his lawsuit against EPA makes no attempt to deny that humans are contributing to climate change.

“This isn’t a religion, whether you believe in climate change or not, and whether man made emissions contribute to it,” Stenehjem said. “It is either a scientific reality or it isn’t. And I think the consensus among those who are experts on it is that it does. But irrespective of that, it is the reality in the world we are going to have to live with. And we’re going to have to contend with it, and we can do that.”

And that reality means while North Dakota is suing over the plan, the state is also working on a way to comply.

“This reduced carbon future is something we will be talking about today, tomorrow, 10 years from now,” Glatt, with the North Dakota Department of Health, told the audience in Beulah. “So we can put our heads in the sand and say, ‘this is so much BS, and we should just ignore it.’ (But) I don’t think we can. We need to take a hard look at this to see what we can do to make this thing work.”