Art Salazar, the director of operations for Green House Data, shows off one of the company’s data vaults, which houses servers and other data infrastructure.

Inside the secured vault at Green House Data are rows and rows of glass and metal cabinets, chock-full of humming electronics and colorful cables.

“This is the cloud,” said Art Salazar, the company’s director of operations, as he led a tour of the building. “You’re standing right in front of the cloud.”

The cloud, where you upload photos and stream video, is real, physical infrastructure, housed in data centers across the country.

A sticky mat removes dirt from people’s shoes at the entrance to one of Green House Data’s data vaults.

Feeding the cloud at Green House Data are big, black power lines, snaking along the ceiling of the room. Like most data centers, electricity is the company’s biggest expense, which is why Green House Data is obsessed with energy efficiency. Among other things, the company has rigorous dust control protocols and an air sampling program designed to catch any undetected inefficiency. But despite that focus on efficiency, Green House Data still consumes a huge amount of electricity—15 million kilowatt hours last year, enough to power more than a thousand average homes.

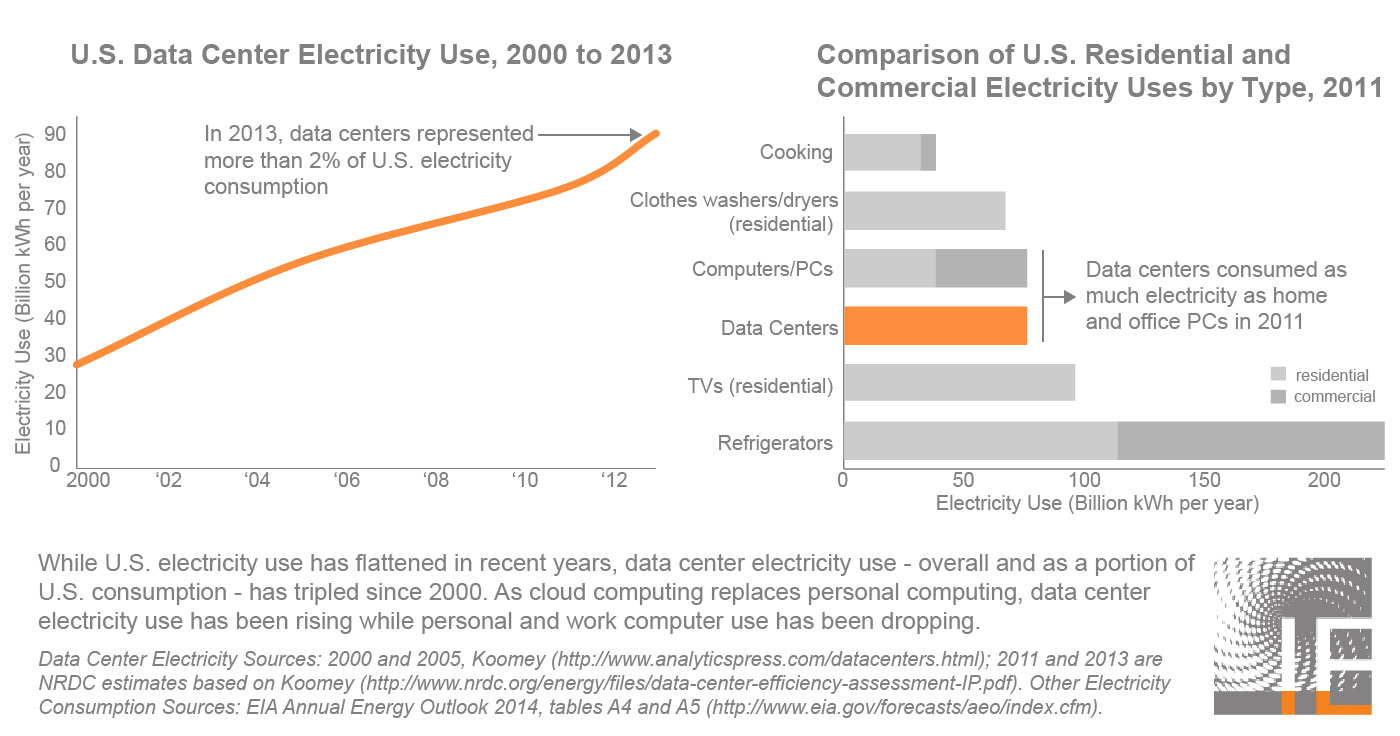

Overall data center electricity consumption is considerably higher. In 2013, statistics compiled by Inside Energy show data centers used 2 percent of all U.S. power—triple what they consumed in 2000.

Get the data: CSV | XLS | Google Sheets | Source and notes: Github

“The electrical resources of the planet are finite, but our need for data seems to be infinite,” said Wendy Fox, Green House Data’s communications director. For that reason, Fox says as the sector grows, it has a responsibility to do it sustainably.

For Green House Data, that means purchasing renewable energy credits, to offset the mostly coal-fired power the company uses from Wyoming’s grid. Similar credits are how many tech companies have managed their carbon footprints in the past, but now that’s changing. Larger companies are now sourcing more power directly from renewables.

“Direct sourcing is important to us because our goal is really the transformation of the electric grid,” said Brian Janous, the Director of Energy Strategy for Microsoft, which owns Wyoming’s largest data center.

How is Microsoft planning to achieve the transformation of the electric grid? Not alone. Microsoft is teaming up with dozens of other companies, including Facebook and Google, to push for easier access to renewable energy. Their leverage comes from the fact that they are becoming larger and larger energy consumers.

“We’re going back to our utility every year and saying,’ We’re going consume more power next year than we did the year before,’” Janous said.

That puts data companies in a unique negotiating position with utilities, and with the states that want to attract their business.

“We want to influence policy, we want to influence the availability of these resources,” Janous said.

It appears to be working. In Nevada, a data company was able to convince the utility, NV Energy, to build new renewable capacity for its project. In Virginia, Microsoft has negotiated an agreement for a new solar farm.

In Wyoming, Microsoft has already invested around a billion dollars in data centers. Shawn Reese, the director of the Wyoming Business Council, hopes that’s just the beginning.

“We want Microsoft to continue to grow here and, frankly, we want their competitors here in the State of Wyoming as well,” he said.

But while Wyoming has great renewable energy potential, very little of it has been tapped. Wyoming law makes it difficult for companies to directly invest in renewable energy, and the state’s utilities don’t offer renewable tariffs for companies.

“The markets are changing, the technologies are changing and the state’s got to keep up with those,” said Reese.

Or risk losing out on business from one of the nation’s fastest growing sectors.

What’s next?

- Listen to our story about the nation’s first wastewater-powered data center, in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

- Look at the real-time electricity usage for one of Facebook’s data centers.

- Check out this map showing states where it is easy for companies to source renewable energy directly.