In fiscal year 2016, the University of Wyoming’s utility bill was $10.8 million—almost $2 million more than fiscal year 2015. Next year, as new buildings under construction come online, that bill is likely to increase, even as the University faces $41 million in budget cuts. That means there may be hard choices ahead—keep the lights on, or keep people employed.

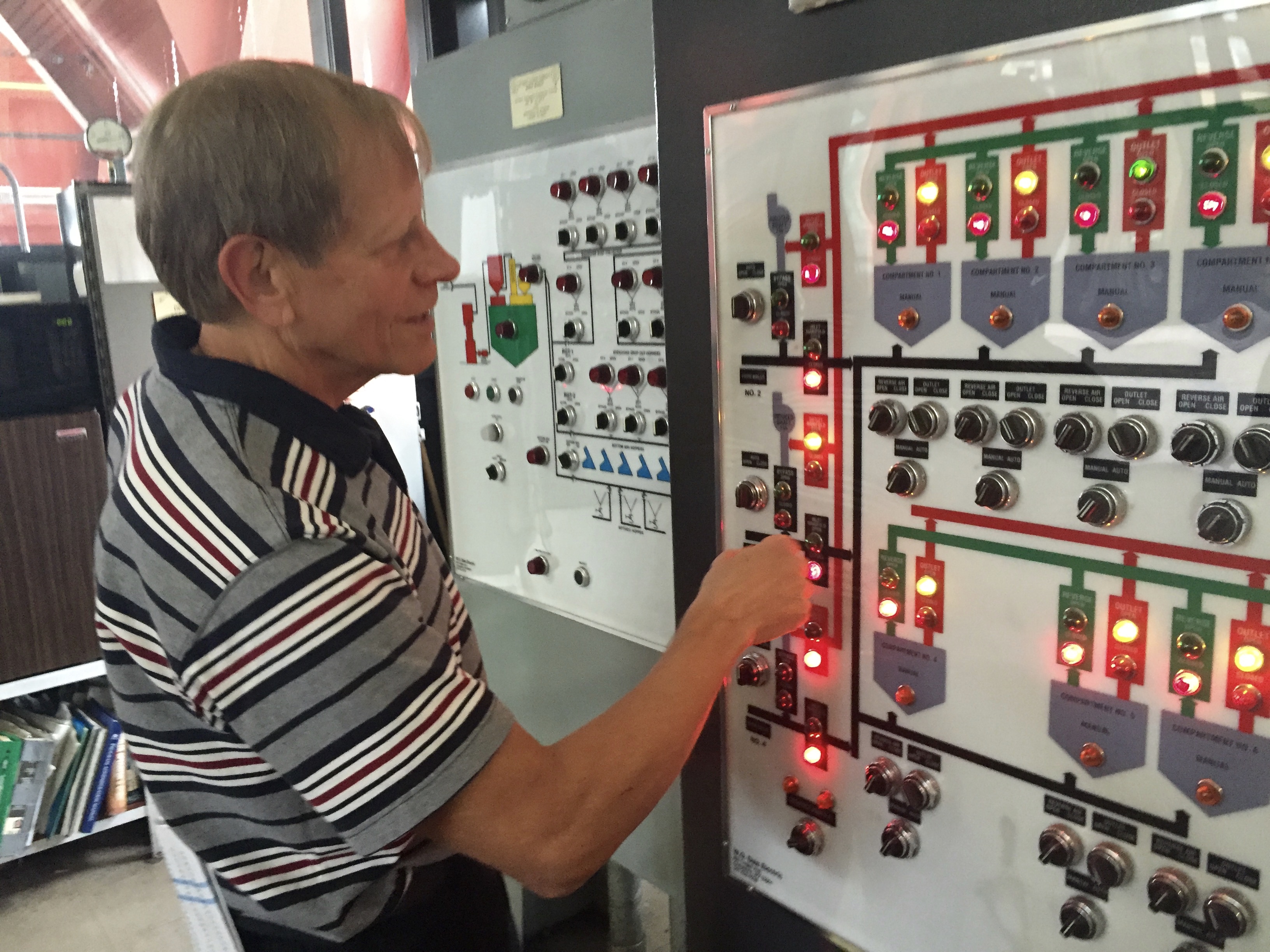

A big chunk of the University’s utility expenditures go towards the Central Energy Plant, a big, glass-walled building on the outskirts of campus. Inside, it is a tangle of pipes and monitors. A loud mechanical rumble pervades the building, occasionally interrupted by ear-piercing alarms.

The plant’s main function is to provide heating and cooling to the campus, which it does with the help of three bright red, two-story tall boilers named Huff, Puff and Wheeze. The boilers suck down coal by the truckload and natural gas by the million cubic feet to generate steam, which is then piped to buildings through miles of underground tunnels.

All that fuel to run the energy plant makes up a major chunk of the University’s utility bill, but electricity is an even larger share. Most of that goes towards the motors that run the air systems in campus buildings.

“Motor loads are something nobody sees—they’re behind the wall,” said Forrest Selmer, the deputy director of utilities for the University. “But if you do things right, you can really save a majority of your electricity through a reduction in motor loads.”

This map shows building footprints for the University of Wyoming in Laramie. Buildings are shaded according to their electricity use (in kWh) per square for the 2016 fiscal year. Darker colors indicate more electricity use. Mouse over or click on a building to see more information, like the cost of electricity, the total energy (including heating and cooling), and the overall utility costs (including water). The engineering building’s electricity bill was the largest, at $322,873. But the Centrex building used the most per area, at 122 kWh, or $9.37 per square foot. That’s more than twice than the next biggest user.

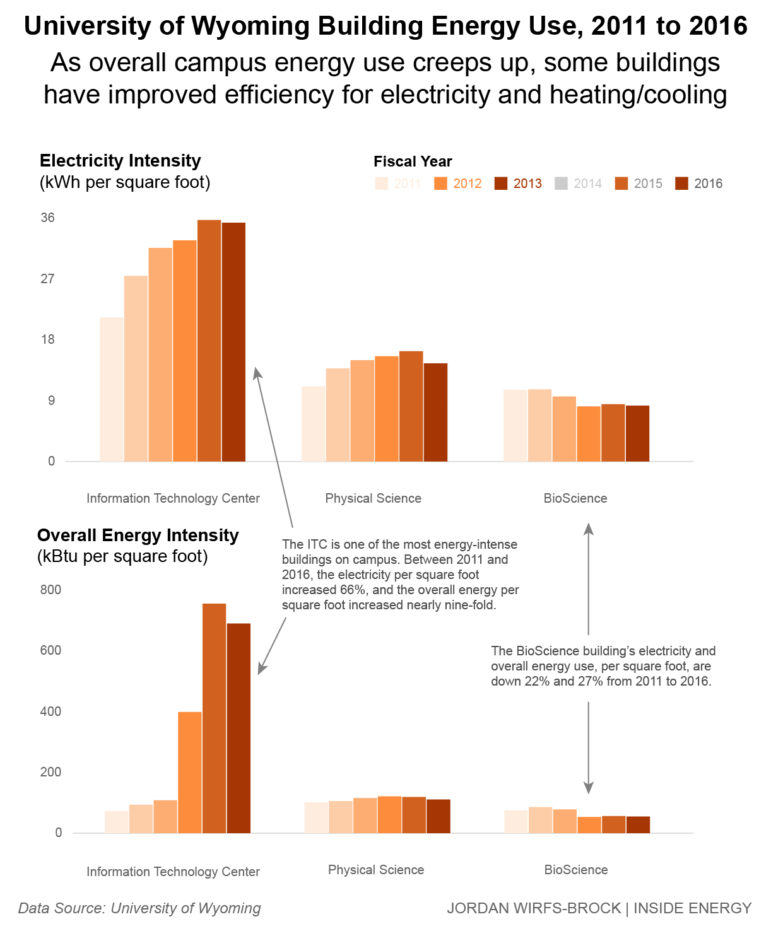

But while upgrades to things like motors can save a lot of money in the long-run, they also cost a lot of money upfront. Recent renovations of the Biological Sciences building replaced the old heating and cooling system and installed more efficient fume hoods in the building’s labs. That cut the building’s energy consumption by a quarter, but it also cost millions of dollars.

Selmer says despite those capital costs, the University has made some big investments to improve energy efficiency in recent years—things like changing out windows and lights and installing electronic controls for heating and cooling in some buildings.

As a result, the University’s average energy intensity per square foot is trending down. Even so, compared to institutions with a similar footprint, Wyoming is fairly average in its energy use. And when it comes to energy per student, Wyoming is well above average, in part because the University has more square feet of building space per student than its peers—not even including new construction.

Selmer says his department does what it can to keep costs down on the mechanical side, but when it comes to trying to change behavior to save energy, he says that doesn’t get as much attention.

“Way back we asked for a sustainability officer and that didn’t go very far,” he said. “It’s not part of anybody’s job duties, this is just extra stuff we do.”

“Way back we asked for a sustainability officer and that didn’t go very far,” he said. “It’s not part of anybody’s job duties, this is just extra stuff we do.”

The University does have a volunteer sustainability committee, made up of faculty and staff. Nicole Korfanta is the director of the Ruckelshaus Institute and the co-chair. Her office is in the Bim Kendall House, which she proudly points out is one of the most efficient buildings on campus.

That efficiency is largely tied to the building’s design and super efficient mechanical systems, but Korfanta says behavior also plays a role—and could play a bigger role elsewhere on campus.

“Given the financial situation at the University, now is the time to really start saving energy,” she said. “That saves us money and that translates into keeping people around—the staff and the faculty who make UW really special.”

Korfanta points to Oklahoma State University as an example of how behavioral changes can translate into big savings. OSU says it has cut its bills by tens of millions of dollars by through a coordinated effort targeting things like turn down building thermostats and shut off unneeded lights.

The University of Wyoming doesn’t have a similar overarching sustainability or energy efficiency strategy. Not only that, the University is rapidly adding more square feet to its footprint.

“There is a history of not fully realizing what the costs are that is about to intersect with some very energy-intensive buildings,” said Bill Mai, the vice president for administration, referring to projects like the new High Bay Research Facility. When those new buildings come online, utility costs will rise.

“It’s something that has to be done,” Mai said. “Those bills have to be paid. We don’t have an option not to pay them.”

Which means continuing to cut in other areas, or looking seriously at ways to make improvements to efficiency on campus.

What’s next?

- Wyoming ranks among the worst states in the nation for energy efficiency. How efficient is your state?

- Visit one of the country’s most energy-efficient buildings with Inside Energy’s Jordan Wirfs-Brock.

- Learn about the National Renewable Energy Lab’s research into energy efficiency for commercial buildings.