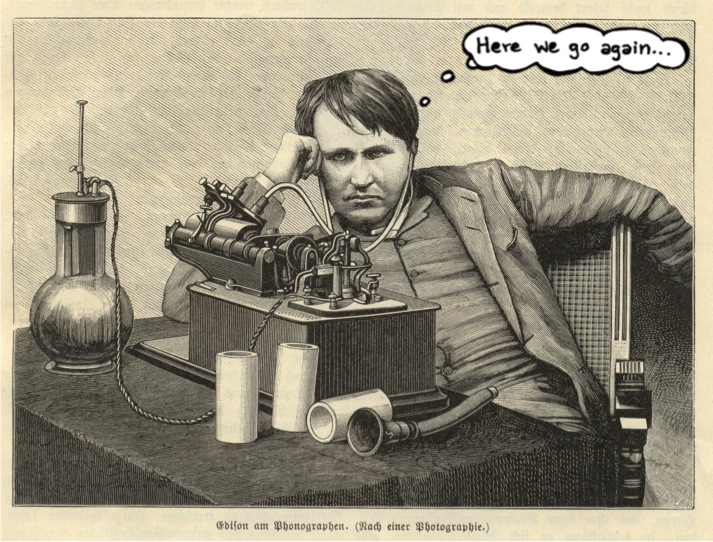

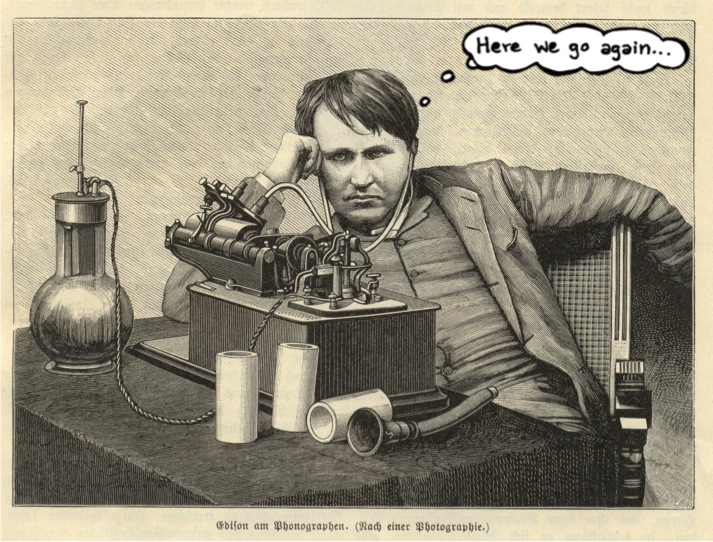

Jordan Wirfs-Brock drew the thought bubble, the picture is public domain

Although Thomas Edison would probably be happy to see decentralized power sources making a comeback, the debate can be exhausting.

This week, Inside Energy is exploring how solar power is changing the way electricity is delivered in the U.S. See the full series here.

A rapidly increasing number of U.S. households are installing rooftop solar panels, and that’s foreshadowing a wider debate over the future role of our traditional electric grid. Ironically, it is a debate we’ve pretty much already had.

In the 1880s, heralded inventor Thomas Edison was locked in a bitter battle with engineer and entrepreneur George Westinghouse over how this new invention of electric power should spread across the country, (a battle commonly known as The War of the Currents.)

Edison, who invented the very concept of electric power distribution, called for a decentralized, widely distributed power system with a bunch of small power plants providing low-voltage direct current (DC) electricity to nearby homes and businesses.

Westinghouse, working with inventor Nikola Tesla, advocated the use of high-voltage alternating current (AC) from a centralized system of large industrial power plants transmitted out to a spiderweb of power lines connecting the entire country.

Westinghouse, AC and the centralized system eventually won out, and that’s more or less the model of the grid we have used ever since. It is a stable, reliable, cheap system, currently threatened by rooftop solar.

A little bit. Maybe. Eventually.

Ryan Pletka works with infrastructure consulting firm Black and Veatch. Right now solar is one of smallest parts of our electricity system, but Pletka sees adoption trends going through the roof:

“If you look at data on the growth rate of solar…it’s almost a flat wall in terms of a spike,” Pletka said.

It is as if Thomas Edison’s original distributed power model is coming back from the dead to battle the Westinghouse system once again. There is even a resurgent call for more DC electrical supplies.

Inside Energy data journalist Jordan Wirfs-Brock has this analysis of net metering rates, a reliable metric for gauging solar growth.

As we’ve also reported, many utilities have been pushing back against rooftop solar*, claiming it is an unreliable, intermittent, resource coming in at various voltages and competing on the same lines with their big power plant electricity. Utilities are lobbying in state capitals and in Washington D.C. to hold rooftop solar back and make it more expensive.

But consultants like Pletka are suggesting that utilities should jump into the solar game–lease panels, sell panels and embrace the change.

“We feel the utilities are in a unique position in the industry where they can proactively respond to distributed generation, particularly solar PV**.”

Some companies, like NRG Energy, are doing just this. NRG Energy operates in almost every state from New Jersey to Wyoming. It is not a utility, but is similar in that it has centralized, old-style power plants and sells that electricity to consumers. But the company will also sell residential solar panels, it will lease them, whatever its customers want.

“(We’re) a power company of choice,” said NRG Home Solar President Kelcey Pegler Junior.

NRG has to compete with other power providers, unlike many utilities. That’s part of why NRG feels more of a need to stay ahead of the curve on distributed solar.

“By the time you recognize that technologies are disrupting, it’s too late,” Pegler said.

Doug Arent works as Executive Director of the Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis at the National Renewable Energy Lab in Golden, Colorado. It is his job to study future scenarios for the electric grid. He’s an optimist, and said it doesn’t have to be an us vs. them, utility vs. rooftop solar owner scenario.

“It’s a collective dialog about how do we collectively move that system forward,” he said.

He thinks this conflict will work itself out in time, that eventually we’ll have a hodge-podge of electricity sources: de-centralized and centralized, DC and AC, Edison and Westinghouse.

Arent believes we’ll still have the major grid, but towns will also have smaller microgrids they can rely on in emergencies, more homes will have battery storage to back up their rooftop solar panels–and utilities will adapt to all of that.

Again, he’s an optimist.

*the reason we use the phrase “rooftop solar” or “residential solar,” rather than just “solar,” is to specifically reference the systems individual consumers are installing that allow them to reduce their dependency on utilities and the traditional grid. It doesn’t matter where they’re installed; rooftop, backyard, by a rock, on a cow–whatever.

Utilities aren’t fighting all solar. The falling price of panels is actually a good thing for them as well, provided they own the generation.

**PV means photovoltaic, the type of solar panels in most rooftop installations.