North Dakota has always been a friendly, easy place to vote. It is the only state in the country without voter registration, and precincts are small enough that poll volunteers often recognize people who come through the door.

“It’s kinda like a reunion,” said Bonnie Fix, who’s been working elections here since 2001. “Kinda like a family picnic.”

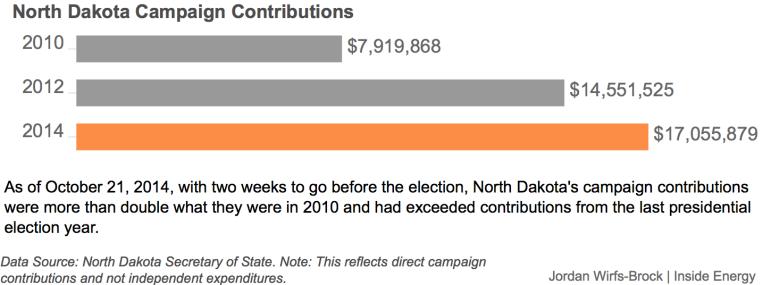

Running for office in North Dakota has historically been equally low-key–and low budget, with winning candidates for state offices raising less than a few thousand dollars each. But the oil boom has changed all that. The 2014 election cycle looks like it will be the most expensive ever in state history, with over $17 million in campaign contributions.

“It’s gotten ugly,” said Jim Fuglie, the former head of the Democratic Party in North Dakota and an active political commentator and blogger. “We’ve never had an industry this big, with this much money, have this much influence on an election.”

Fuglie believes the tone of politics has changed, too, and points to negative campaign ads like the one calling Democratic candidate for Agriculture Commissioner, Ryan Taylor, a “tree-hugger.”

The ad, which ran on commercial radio stations leading up to the election, was paid for by a local political action committee or PAC, funded by the national Republican State Leadership Committee. Some of their top donors are oil and gas companies like Devon Energy and ExxonMobil.

North Dakota takes a folksy approach to encouraging residents to vote.

Between PACs, trade groups and corporations, the oil and gas industry has spent $1.3 million on the 2014 election in North Dakota, according to data from the North Dakota Secretary of State. Some races matter more to the industry than others–like the Agriculture Commissioner race. While the title sounds irrelevant to oil and gas, as one of three officials who sit on the state’s Industrial Commissin, the Ag Commissioner has a lot of power to regulate the oil and gas industry. So far, the oil and gas industry has kicked in $73,000 to support Republican Doug Goehring–about a quarter of all the money he’s raised. They’re worried that if Taylor, the Democratic challenger, wins, he’ll slow down the pace of development.

“The oil and gas industry has been somewhat successful in characterizing any questioning of the speed as potentially threatening everything,” said Nicholas Kusnetz, a reporter with the Center for Public Integrity who’s written extensively on the industry’s influence on politics in North Dakota.

There’s another issue, however, that’s attracted even more money, both from the oil and gas industry and and others: The North Dakota Clean Water, Wildlife and Parks Amendment, also known as Measure 5. Measure 5 would create a constitutional amendment setting aside five percent of the oil extraction tax for conservation projects. Even though it doesn’t create new taxes, the oil and gas industry strongly opposes it.

Ron Ness explained why. He is President of the North Dakota Petroleum Council and said oil companies want to see as much money as possible go directly to the boomtowns – fixing roads and building schools and housing. “The more oil tax money going back to those communities helps to attract and retain workforce,” he said.

The American Petroleum Institute has also weighed in, calling Measure 5, “a disservice to the state’s economy and its residents.” To help defeat it, API has spent over a million dollars on yard signs, magnets and a slick website. And it’s sponsoring phone calls. Carmen Miller is the Director of Public Policy for Ducks Unlimited, a conservation group backing Measure 5. She knows about the anti-Measure 5 phone bank, because she received a call.

“If you’re calling the proponents of the measure, you must be calling just about every phone number in the state,” she said.

Yard signs paid for by the American Petroleum Institute on a street in Bismarck, North Dakota.

It’s not just oil and gas companies that are spending heavily on this election. National conservation groups like Ducks Unlimited and The Nature Conservancy have kicked in a combined $4.8 million to support Measure 5. Miller wouldn’t comment on whether proponents of Measure 5 had planned to spend that much initially, or if they had upped their spending in response to oil industry donations. But four days after American Petroleum Institute spent its million to defeat the measure, The Nature Conservancy chipped in $600,000.

Democrat Ryan Taylor has raised nearly $300,000 for his campaign to become Ag Commissioner — about a quarter from out-of-state donors. That’s more than twice as much as was raised by the winning candidate in 2006.

For Bob Harms, the chairman of the North Dakota Republican Party, the levels of spending are indicative of how much money is now flowing into state coffers. The state gets about $9 million every day in oil tax revenue.

“We have more money to fight over,” he said, “and we have more money to fight with.”

The level of national interest in state politics doesn’t sit well with some North Dakota lawmakers, who have another measure on the ballot this fall that would prevent constitutional amendments that appropriate public money for a specific purpose — like Measure 5 — from ever appearing on the ballot again.

“With our newfound prosperity, we think there are a lot of organizations like (Measure 5 proponent) Ducks Unlimited who see our surplus as an opportunity to divert money for their special purposes,” State Senator David Hogue, R-Minot, told The Forum News Service.

All this political money marks a big change for the state. For generations, North Dakota was a poor, sparsely populated state whose residents left for work and often never came back.

“This was a very quiet agricultural state that wasn’t really on the national radar in any sense until a few years ago,” Kusnetz said. “Now suddenly it’s national news, and it’s really all because of one industry.”

What’s next:

- Explore oil and gas companies’ contributions to North Dakota elections and see industry contributions to state elections nationwide at the National Institute on Money in State Politics.

- Read reporter Nicholas Kusnetz’s story on the influence of the oil and gas industry in North Dakota.

- Learn more about Measure 5, the North Dakota Clean Water, Wildlife and Parks Amendment.